Feature photo: A group of women whose husbands were killed in the 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom; in Trilokpuri area of East Delhi; by Guari Gill via New York Times.

by Lakhpreet Kaur

Introduction

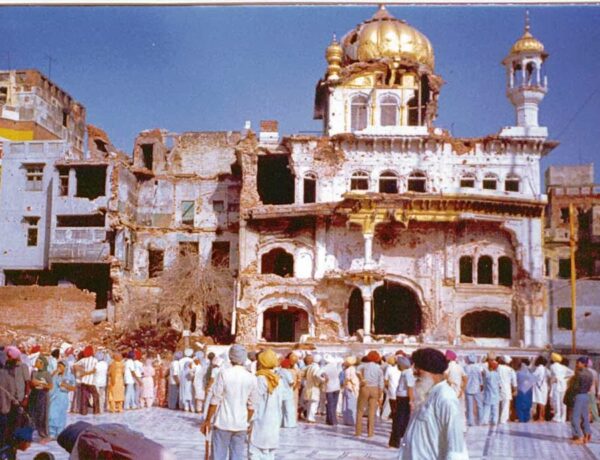

In early June of 1984, the Indian Army invaded Harmandir Sahib under the orders of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to “flush out Sikh terrorists”; the official name was “Operation Blue Star“. During the invasion, the army killed thousands of Sikh civilians. Then on October 31, 1984, after the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the Indian Government orchestrated anti-Sikh pogroms across India which lead to the murder of thousands more.

In the Sikh Panth, these attacks are colloquially referred to as “1984” and have shaped the collective Sikh psyche.

This series of three articles hopes to serve as a brief introduction to the events of 1984 and to provide a starting point for those interested in learning about the historical events. So the information is accessible to everyone, we will not be sharing graphic descriptions or triggering details. Rather, we will share with you resources where you can read eye witness accounts, if you are interested.

Before we start, we would like to take this opportunity to honor the Singhs and Kaurs affected by the violence of 1984, and the shaheeds who laid down their lives defending the Panth.

Part 1: The Anti-Sikh Violence of 1984 | The Background

Part 2: The Anti-Sikh Violence of 1984 | The Battle of Amritsar (aka Operation Bluestar)

Part 3: The Anti-Sikh Violence of 1984 | Anti-Sikh Pogroms

Part 3: Anti-Sikh Pogroms

In response to the attack on Harmandir Sahib and the impunity Indira Gandhi enjoyed, her bodyguards, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, administered justice and assassinated Indira Gandhi with their service weapons on Oct 31, 1984. Beant Singh was shot to death (achieving shaheedi) during his interrogation in custody soon after the assassination. Satwant Singh and co-conspirator Kehar Singh were arrested and hanged (achieving shaheedi) on Jan 6, 1989. In his court statement, Satwant Singh appealed for an end to communal violence in the country, while pinning the blame for the same on Indira and Rajiv Gandhi.

The day following Indira Gandhi’s death, on November 1, 1984, state-sponsored anti-Sikh pogroms (violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling a specific ethnic or religious group) began.

To exacerbate communal tension and fuel public violence, the government circulated rumors upon announcing Indira Gandhi’s death. For instance, they claimed that Sikhs en masse were distributing sweets to celebrate her death, Sikhs had poisoned the drinking water of Delhi, and Sikhs had slaughtered Hindu train passengers, (Kaur, 2004). This was coupled with official support of violent mobs; the ruling Indian National Congress Party organized, armed, and incited violent mobs to murder, rape, and torture Sikhs, and to loot and destroy their homes, neihgbhorhods, businesses, and gurdwaras. The violence lasted for several days in Delhi and across 40 cities in India.

Police forces were either absent from the scene, observed the violence, or actively participated in it. “The words of a senior police officer who testified before the Misra Commission (a commission setup to investigate the pogroms) substantiated the mass organization of the pogroms: ‘The riots were engineered to teach Sikhs a lesson.’,” (Kaur, 2004, pg. 45).

By November 3, the violence had ended.

Government estimates project that about 2,800 Sikhs were killed in Delhi and 3,350 nationwide, while independent sources estimate the number of deaths at about 8,000–30,000 Sikhs were killed. The Government estimates that 20,000 Sikhs were displaced and made homeless in Delhi while independent sources estimate 50,000 Sikhs were displaced, (Kaur, 2004). Many women were made widows and were subject to physical and sexual violence by the mobs.

Some Sikhs who survived credited their non-Sikh neighbors with providing them with shelter.

Justice

Individual perpetrators of the violence, whether civilians or government officials, were not prosecuted (Kaur, 2004) for their crimes of 1984. In 2011, Human Rights Watch reported that the Government of India had “yet to prosecute those responsible for the mass killings.”

According to the 2011 WikiLeaks cable leaks, the United States believed that the Indian National Congress’ was complicit in the violence and called it “opportunism” and “hatred” by the Congress government of Sikhs.

1984 Aftermath

The events of 1984 were related to and resulted in several large events:

- Thousands of Sikh soldiers mutinied or resigned from their positions in protest to the attacks.

- Many prominent Sikh leaders and theologians who had been honored by the Indian government returned their medals and certificates.

- Several soldiers and generals involved in Operation Blue Star were presented with gallantry awards, honors, and decoration stripes.

- June – Sept 1984: The Indian Government carried out the military operation, Operation Woodrose during which thousands of Sikh youth and civilians were rounded up, detained for interrogation, subsequently tortured and, in some cases killed.

- 1980s – Operation Shudeekaran – The Indian Army tortured Sikh women as a way to force Singh freedom fighters to surrender.

- In 1986, General Arun Shridhar Vaidya, the Chief of Army Staff at the time of Operation Blue Star, was assassinated by Harjinder Singh Jinda and Sukhdev Singh Sukha. Both were sentenced to death, and hanged (achieved shaheedi) on October 7, 1992. They wrote this letter to the President of India before their execution.

- In 1989, resolutions were introduced in the US Congress, in both the House of Representatives (H. Con. REs 343) and Senate (S.Con.Res.150) – A Concurrent Resolution Concerning Human Rights of the Sikhs in the Punjab of India. This resolution expressed the sense of the Congress that India should allow Sikhs full access to the Golden Temple and remove all military presence from the shrine. It urged the Government of India to use restraint in resolving the dispute with the Sikh people in the Punjab, and called for a political solution to restore home rule in the Punjab, with religious freedom and human rights guarantees. Concurrent resolutions, such as these, do not have the force of law, and are used to simply express the sentiments of both of the houses.

- 1986 January – a Sarbat Khalsa convened at Harmandir Sahib in response to the 1984 attacks. A Gurmata declares Khalistan as an independent nation.

- 1986 April – Operation Black Thunder I: The Indian Government again entered Harmandir Sahib to kill/capture pro-Khalistan leaders and militants.

- 1988 May – Operation Black Thunder II: The Indian Government again entered Harmandir Sahib to kill/capture pro-Khalistan leaders and militants.

- 1990s the Sikh and Punjabi human rights struggle continued. Human rights defender Jawant Singh Khalra emerged as an activist and spokesperson for Sikhs who have been disappeared by the government after his discovery of mass cremations of Sikhs throughout Punjab.

- 1980s and 1990s – More Sikh women started to wear the dastar with many citing its adoption as a political statement and to show solidarity to the Singhs struggling for liberties in Punjab, (Mahmood & Brady, 2000).

- 1990s – the Indian Government Systematic continues the extrajudicial killings of Sikhs all across Punjab.

- Since 2015, state senates in California, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Connecticut have pass resolutioned condemning the 1984 anti-Sikh riots as “genocide”.

Context

Punjab has been struggling to establish human rights and autonomy for decades. Sikhs and Punjabis clamoring for civil liberties have been met with government resistance. Mallika Kaur writes that, “Punjab was the arena of one of the first major armed conflicts of post-colonial India. During its deadliest decade, as many as 250,000 people were killed.” June and November 1984 were just two instances of such violence.

With his muder, Baba Jarnail Singh was cemented as a folk hero and shaheedi in the Sikh community. Some say this, along with the anti-Sikh Pogroms of November 1984, intensified the Punjabi & Sikh rights movement into the 1990s.

1990s

Violence against Sikhs did not end in 1984. According to ENSAAF, in the early 1990s the Indian Government shifted its state violence, “from targeted lethal human rights violations to systematic enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions, accompanied by mass illegal cremations”.

During this time, Punjab security forces engaged in operations that “included widespread and systematic human rights abuses such as torture, disappearances, and extrajudicial executions, which claimed an estimated 10,000 to 25,000 lives,” reports ENSAAF. “….Director General of Police (Punjab) KPS Gill expanded upon a system of rewards and incentives for police to capture and kill militants, leading to an increase in disappearances and extrajudicial executions” of civilians, advocates, activists, and militants. “Hundreds of perpetrators, including all of the major architects of these crimes, have escaped accountability.”

Why do we need justice?

It is essential to pursue justice in order to assert human rights, to honor the victims and survivors of 1984 violence, and to affirm the personhood of Sikhs of today. Part of the healing process (for individuals and the Panth), and a path to reconciliation, includes acknowledging and addressing violence experienced by individual Sikhs and the larger Sikh panth. This could mean working towards restoring losses such as economic, financial, or religious. Seeking and achieving justice can also help mitigate intergenerational trauma that lingers in our community.

Furthermore, without the Indian Government taking responsibility for the violence of 1984, it develops a culture of governmental fascism, encourages extreme right-wing Hindu nationalism, and excuses acts of religiously targeted violence through impunity. This in turn promotes an environment of oppression against all religious minorities across India.

Why should we learn about 1984?

Knowing the events of 1984 help us understand the state of the Sikh Panth today. It helps explain the feelings of solidarity, sovereignty, and justice that bind us together. It helps us understand the complicated relationships many Sikhs have with India. It helps us understand why many of our sangat members are still hurting.

By learning about the violence of 1984, we can start to understand the role that dehumanization, prejudice, and discirmination have in society. The events of 1984 illustrate how fragile the social systems we rely on for safety are when humans are fearful and are looking for a scapegoat. It also illustrates human’s potential for extreme violence as well as extreme love. With this background, we can start working towards creating a society built on truth, justice, and love.

What you can do

There are a few things you can do to support the victims and survivors of 1984 violence. Here are a few ideas:

- Learn and discuss the events of 1984.

- Donate to or volunteer with ENSAAF – a nonprofit organization working to end impunity and achieve justice for crimes against humanity in India, with a special focus on Punjab.

- Work on healing your own intergenerational trauma.

- Donate to or volunteer with organizations that address the symptoms of trauma, such as depression and alcoholism.

Continue Reading

Part 1: The Anti-Sikh Violence of 1984 | The Background

Part 2: The Anti-Sikh Violence of 1984 | The Battle of Amritsar (aka Operation Bluestar)

Part 3: The Anti-Sikh Violence of 1984 | Anti-Sikh Pogroms

More Resources

- Brahma Chellaney’s articles

- ENSAAF Publications

- “Faith, Gender, and Activism in the Punjab Conflict: The Wheat Fields Still Whisper,” by Mallika Kaur

- “Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants” by Cynthia Keppley Mahmood

- “Lost in History: 1984 Reconstructed” by Gunisha Kaur

- Sikh Research Institute

- “The Valiant – Jaswant Singh Khalra” by Gurmeet Kaur

- Widow Colony Film

- “Gallant Defender” by A.R. Darshi

- “When a tree shook Delhi: The 1984 Carnage and its Aftermath” by Manoj Mitta and HS Phoolka

Main Sources

- Singh, Jagjit. (1981) The Sikh Revolution.

- Singh, Khushwant. (1999) A History of the Sikhs. Volume 2: 1839 – 1988.

- Kaur, Gunisha. (2004). Lost in History: 1984 Reconstructed.

- Mahmood, Cynthia and Brady, Stacy. (2000). The Guru’s Gift: An Ethnography Exploring Gender Equality with North American Sikh Women.

Special thanks to:

Dr. Mohan Singh Dhariwal, Darsh Singh, and Princepal Singh for their support and insights in writing this article.

Feature photo: A group of women whose husbands were killed in the 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom; in Trilokpuri area of East Delhi; by Guari Gill via New York Times.