by prabhdeep singh kehal

prabhdeep singh kehal reflects on how we as a Sikh community retell our histories and narratives. They ask the questions of “What do you glamorize and why? What’s left out in the valorization of our storytelling? What harm are we causing? How are our current narratives and historical outlooks about land in line and out of line with Sikh Gurmat teachings?” prabhdeep uses the concept landownership as an example to explore these questions.

“My intention with this discussion has been to begin (for some) and continue (for others) the conversations on creating practices to narrate our histories with purpose and not simply through valorization in US-based youth programming. Otherwise, what imagined world are we pretending to inhabit, while informing youth that our imagined world is reality? One way to begin this exploration could be… if we asked, ‘What is the role of land in Sikhi and how could Sikhs relate to land that does not already define it through ownership?’ Asking these questions openly brings us closer to narrations of our own histories with attention to linked intergenerational violences and gets us towards intergenerational organizing.”

⠀⠀

Narrating history: For What do we Narrate?

We often talk about violence inflicted upon our Sikh communities through very specific topics of genoicde or hate crimes in the US. But, how do we – people who wish to create a collective Sikh sangat (linked communities in fellowship together) – talk about violence that happens within our communities? Especially when we retell our Sikh histories?

On one hand, we may not agree on the type of harm that occurred – material, spiritual, intellectual, or cultural. Yet, on the other hand, we may not agree on whether something in particular can be harmful. Not to mention that we maintain an air of silence around violence in many Sikh spaces for different reasons. Across geographical Sikh communities, a culture of silence around violence can mean different things. It can be the norm for safety to silence dangerous topics – “don’t bring that up” – and for harm – “that is shameful”, “cover up her body”, or “hide the queer”. When silence can be a tactic for safety and harm in the present, how do we narrate Sikh histories that are filled with silenced violence done towards us, as Sikhs, and silenced violence done towards others, by Sikhs?

In other words, how do we continue the process of updating our communal stories without an indulgent sense of self-interest? As differing political groups and actors can have their own stakes for producing specific narratives, as Sikhs, for what do we narrate? As one example, I’m going to take a look at Maharaja Ranjit Singh and land-ownership and its relationship to some US-based programming. This is primarily an intra-Sikh communities conversation, but there may be connections or similarities for readers who have experienced other faith traditions; that said, let us collectively be mindful of interpretative limitations.

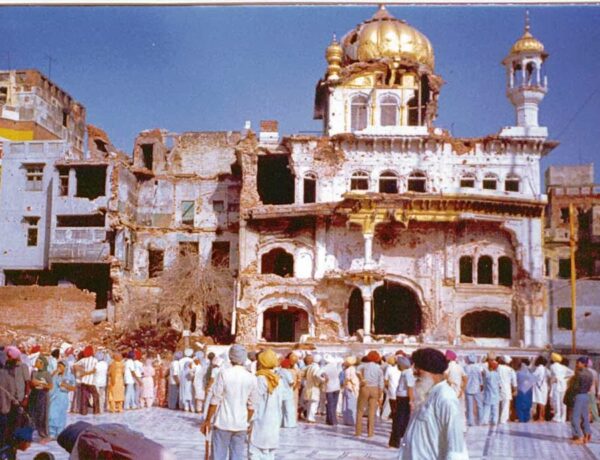

Reflecting On A Context: Youth Programming

While growing up and observing Sikh youth programming from the other side of the room (I kept a distance that felt safe to me), Sikh youth camps and Gurmat-oriented conferences valorized specific aspects, periods, or figures of our past. Sevadars told stories that celebrated all aspects of our history and glorified all Sikh actions. For instance, we had discussions of how Sikhs in the 1800s consolidated land, territory, power, and identities to form a government under Maharaja Ranjit Singh – in the form of an “empire”, “nation”, “dynasty”, or “kingdom”. Yet, we do not talk much about how this consolidation happened. I rarely, if ever, heard conversations that talked about the nuances of his land reforms, which could contextualize how political decisions during his reign were linked to inequalities preceding and following his reign. Within intra-community conversations, when we discuss how many of our families may have gained economic benefits or land rights to pass along to their future generations, there is not always communal language available to understand this outside what we may learn in US elementary curriculum. Instead, I usually experience tactics within our sangats that I would refer to as “narrative valorization” to discuss Sikh histories in a particular way, or what sociologists call “cultural boundary work”. Depending on the speaker, this practice can be erasure of violence, at worst, or constructed ignorance around violence, at best. While I never expected youth program instructors to be historical experts, there were also very few resources available for me to think about these questions myself in the programming at the time. Later in life when I decided to think about his reign (and when I had time to do so), I found how I wished this history could have been introduced to me through our communal histories.

Evaluating A History: Gender and Property In Sikh Inheritance

Another way Maharaja Ranjit Singh is often fondly revered is for his gendered land reforms. How can we understand this narrative, and not simply through usual frames of valorization? I give one interpretation of the historical record.

In her recent book, Royals and Rebels: The Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire, historian Priya Atwal analyses specific ways that gender operated within the territorial politics of the Maharaja’s court. As political leaders consolidated territory, there were questions on inheritance. When analyzing one instance of gendered and casteist norms of property inheritance when the Maharaja seized “the Nakai properties”, Atwal notes,

“Kinship ties were clearly being manipulated in this incident to overturn the hierarchy of relations between the Maharajah and his in-laws. Kharak Singh, though younger in age [and son of the Maharajah], was made to displace his uncle as the head of his maternal family, thereby superseding [Kahan] as heir and owner of the Nakais’ property” (73).

This was significant because, as Atwal continues,

“This was a bold act of interference, rewriting norms of misl succession; Ranjit Singh was effectively claiming that the female line now attached to his dynasty should be deemed superior to the Nakai’s male line, and replacing the traditional mode of landed succession… with the inheritance of all property by the son of the clan’s daughter” (73).

In this incident, while the Maharaja inverted the existing caste-based and misl property norms to uplift a female lineage line for inheritance, it was his own line that he uplifted against other elite political actors. While he challenged this dimension of patriarchy in an elite setting, he also consolidated the rewards. Rather than relying exclusively on war, the Maharaja also used misl norms strategically to consolidate power into his own lineage, similar to actions of other land-owners of the time who could be from different faith traditions and caste locations.

Yet, not all costs can be afforded. Atwal discusses that an additional reason this property debate was significant was because some descendants of Guru Nanak Ji supported Kahan Singh’s claim. Whether Sikhs of that time valued this hereditary lineage because they believed in some divinity of bloodline (i.e., caste-based logics) or simply because they associated the families with Sikh Gurus and deference, these descendants had influence. Because the Maharaja had an awareness of Sikh politics and understood that Guru-affiliated lineages held (and still hold) cultural communal influence, the Maharajah “still recognized that his actions against other Sikh sardars could easily backfire on him if they appeared too harsh” to key actors (74). While more knowledge and research has been emerging about how benefits and harms of his rule were distributed to those within the Kingdom, for those of us interested in comprehensive narratives of our histories, we also consider how the Maharajah’s kingdom was a site of gendered violence. This too is part of the narrative.

Reconsidering a Relationship for Programming: Property for Whom?

How would our individual and collective understandings of Sikhi and Sikh histories be different if we had a way to narrate these experiences as part of our linked communal diasporas, rather than the strict or simplistic frames of valorization? While territorial histories are often discussed through Sikh martial history, it has almost exclusively been under the lens of military power, which is only one lens within Sikh philosophies. At the start, I had asked, “For what do we narrate?” In engaging our historical narratives with a desire to not produce hagiographies through youth programming, we could imagine and work towards a reality of building Begumpura as a sangat, for instance.

I’ve talked about one instance of taking land among an elite group of actors and discussed how dynamics of gender and faith worked to rationalize and transfer property ownership among these elites. What of land or other forms of material wealth that were taken from much less empowered communities and given to these elites as the Kingdom rose? While some descendants may want their ancestors’ land back as some indigenous people in the Americas do, others may simply want to use the land differently than how it is used and not use notions of ownership. Why is this type of relationship with the land, which Sikhs did have, not narrated as part of our Sikh and/or Punjab-based histories?

I bring this discussion up not as an abstract conversation to have over chai. It can have real-life implications like in the case of the Kisaan Mazdoor Andolaan. The Kissan Mazdoor Andolan (farmers’ protest) has been ongoing and figures like Banda Singh Bahadur and his policy of land redistribution have been invoked. These invocations of Banda Singh Bahadur were particularly significant as conversations regarding casteism and land ownership themselves have been sidelined in the movement’s overall demands. Which begs the question for all of us, do we as a community truly understand Banda Singh Bahadur’s land reforms and why people may be using them today? If we read these invocations in the context of this article’s discussion, we could narrate and discuss the end of owning land as property as a Sikh policy within our Sikh histories. But conversations like this can only happen if we understand and discuss our histories and our changing politics as a process that changed over time with others, and resist indulgent narrations (i.e. pick-and choose the stuff that makes us feel good).

My intention with this discussion has been to begin (for some) and continue (for others) the conversations on creating practices to narrate our histories with purpose and not simply through valorization in US-based youth programming. Otherwise, what imagined world are we pretending to inhabit, while informing youth that our imagined world is reality? One way to begin this exploration could be with the topic of this article. What if we asked, “What is the role of land in Sikhi and how could Sikhs relate to land that does not already define it through ownership?” or “How are our current narratives and historical outlooks about land in line and out of line with Sikh Gurmat teachings?” Asking these questions openly brings us closer to narrations of our own histories with attention to linked intergenerational violences and gets us towards intergenerational organizing. In the context of “land”, we could ask, for what do we need or want land?

In the meantime, these questions also invite those of us in the US to work with indigenous people in our locales who are fighting for their own land rights against colonizers and capitalists by challenging notions of “ownership”. This may sound eerily familiar, but in a new way, to some Sikhs, as it links to many kisaans and mazdoors across the globe fighting for their livelihoods with the land.

This piece was written in sangat-based conversations with Harleen Kaur, Palvinder Kaur, Guntas Kaur, manmit singh, and Rita Dhamoon.

About prabhdeep

prabhdeep (they/them) is a writer, community scholar, and educator (and Kaur Life Board Member!). As a sociologist and doctoral candidate at Brown University, prabhdeep researches how people and communities make knowledge about race and racism, and how they use this knowledge in their lives. In their academic work, they broadly question how colonialism persists within US higher education and, specifically, how these ideas about race are used in the processes of hiring, promotion, and defining merit (what counts as good) in academia. prabhdeep’s community-based work focuses on working with others within the global Sikh diaspora to identify and fight how white supremacy, anti-queerness, and gender conformity emerge in our lives. At Kaur Life, prabhdeep will be using their training as a historical and cultural sociologist, along with their Gurmat-based practices of Sikhi, to foster transnational conversations on gender, sexuality, and casteism, and the intersections therein.

No Comments