By Mallika Kaur

Note: This post refers to sexual and other forms of intimate partner violence. While it deliberately avoids any graphic descriptions, it is perfectly normal for some small detail that is innocuous for one person, to trigger or distress another. Please refer to the resources listed below should you feel the need to reach out for support.

“I’m that girl who everyone is talking about,” her voice quiet, but convinced. She then left her phone number on our newly launched Sikh Family CenterHelpline saying, “Anytime is a good time to call,” and hung up. This was just about nine Vaisakhis ago.

April marks the birth of the Khalsa: the culmination of the Gurus’ project of bestowing power to the people. Guru Gobind Singh ji went to great lengths to visually and viscerally etch in our psyche the basic Sikh principles of leader-follower, of humble power, of fearless love. Beautiful basic building blocks of any relationship, family, community, kaum (nation).

Sexual Assault Awareness Month

April is also sexual assault awareness month in the United States.

Some are skeptical (if not sick) of “awareness” months. A single month does not and cannot validate or heal or provide safety. It’s fair to wonder, what should we be doing beyond “awareness”?

I’m taking this opportunity to reflect on how Sikh Family Center’s commitment has grown to increase awareness about the various ways in which we all could possibly be part of the solution, working towards a world without the plague of sexual violence.

Sikh Family Center Helpline

When that call came in 2012, we had recently listed our Sikh Family Center Helpline number on community needs assessment surveys we were conducting in local gurdwaras and sangats. This short message was our first from someone who opely identified as a rape victim-survivor. Sexual violence remains, across all communities, deeply under-reported.

For the next year, we worked with this young woman and her family. They were reeling from the violence inflicted against her by someone a few years older, but many times more powerful -in terms of community influence, and “reputation.” Indeed, he had attempted to ensure she became the girl everyone was talking about. When her father, who was staunchly in her corner, had stood up to tell her truth and demand justice, mud-slinging followed. One woman in her sangat told me casually, “Jeans paa ke aandi si gurdwarae” – She wore jeans to gurdwara. But other older women stood in her corner, even if quietly.

Working with this young woman, like with so many in the years since, alternately enraged and endeared us to our Sikh community in the United States. There are so many hues, with so many unexpected allies (not all “aunties” are oppressive gossips; not all “traditional Punjabi Sikh dads” are regressive, etcetera). As well as so many heartbreaking detractors who collude with abuse (college degrees and accented English do not make you “modern;” money certainly does not make you braver, etcetera.)

Here’s what this young woman told me she wished she had known better and wishes for you to know: the danger was posed by those in her closest orbit. She had always been told to be wary of “strangers,” not of friends.

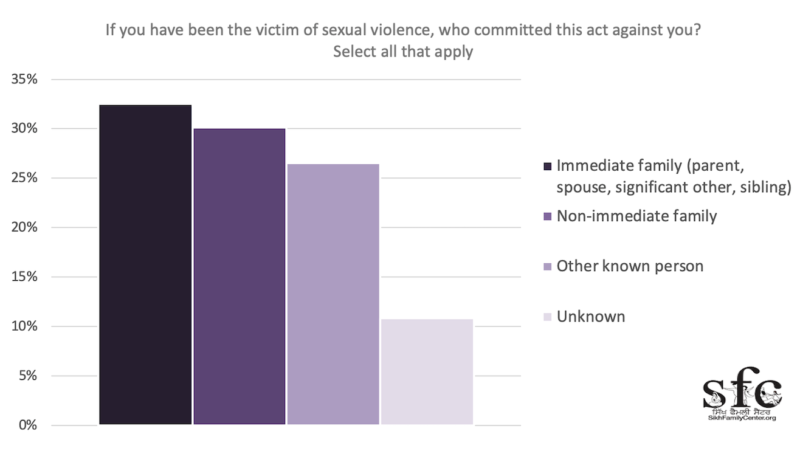

Indeed, all research shows that the majority of sexual violence survivors report being harmed by someone they know. RAINN, the largest anti-sexual violence organization in the United States, reports 8 out of 10 sexual assaults are committed by someone known to the victim. Our Sikh Family Center community-needs assessment of 500 Sikhs across the U.S. showed this number was 9 in 10.

Fast-forward to 2015.

The horrendous Stanford rape case sent ripples across the country, including through circles of Sikh parents with college-age children. Sikh Family Center got some calls—as the only U.S. Sikh organization focused on gender-based violence we regularly get calls for consults and technical assistance from other Sikh orgs and individuals. This time the ask was something we could respond to publicly: help us speak with young people about safety in a community-appropriate way. However, sadly, too many of these requests were focused on only speaking to “our girls” about keeping themselves safe. Rather than speaking to all of our young people about keeping each other safe; about never violating someone’s trust, boundaries, or consent; about truly walking the Khalsa talk.

Sehj Series

Thus was born Sikh Family Center’s college workshop specifically focused on consent: Sehj Series. Today workshop 1 of Sehj Series and the Facilitator’s Guide (updated last year to be Zoom only) is available for all to download.

The idea is to give young college students the space, led by other college students trained and supported by Sikh Family Center’s crisis counselors, to pause and think about boundaries and healthy relationships, platonic or otherwise. It is also a way to increase access to information, resources, and support for those being victimized within relationships (however casually or seriously defined).

We are able to prompt discussions about power and control that go beyond thinking of intimate partner violence in discrete piecemeal terms as physical violence or mental violence or sexual violence.

In my experience, a particularly useful framework to keep in mind is one of “coercive control” (first coined and popularized by the work of Dr. Evan Stark in 2007).

This model appropriately describes the majority of relationships marked by abuse: assaults are “non-injurious, relatively minor, and fall far below the radar of an injury-based model.” The cumulative nature of controlling behavior creates the long-lasting damage. The coercive control model does not look only for specific violations of physical integrity (one abuse tactic among many). It encourages us to look for violations of individual liberty (think: “Where are you going?” “Why are you late? did you take a detour?” “Who are you texting? why won’t you show me if you have nothing to hide?” “Are you seriously wearing that?” “Why do your parents keep calling?” “Do you seriously need a second helping of food?” “Why are you taking that job?” “Why can’t you satisfy me in bed, what is wrong with you?” “Is that how you dance with strangers?”) Dr. Stark noted that “what men do to women is less important than what they prevent women from doing for themselves.”

In the midst of the pandemic, California became one of the recent jurisdictions to adopt “coercive control” into its laws. The examples included now (Section 6320 of the Family Code) are examples that may ring true for you or someone you know?

- “(1) Isolating the other party from friends, relatives, or other sources of support.

- (2) Depriving the other party of basic necessities.

- (3) Controlling, regulating, or monitoring the other party’s movements, communications, daily behavior, finances, economic resources, or access to services.

- (4) Compelling the other party by force, threat of force, or intimidation, including threats based on actual or suspected immigration status, to engage in conduct from which the other party has a right to abstain or to abstain from conduct in which the other party has a right to engage.”

Being aware of these signs early in a relationship—for one’s self or one’s friends—may prove to be helpful. Being aware that these behaviors are decidedly against all Sikh principles can be very validating for those who have faced disbelief, derision, denial, and thus dehumanization in Sikh-looking and Sikh-sounding spaces.

Over the years, we have recognized in conversations with young people the need to tease out the difference between actually living a Sikh life versus merely performing cultural and communal expectations and just looking like a Sikh. For example, participants in the Sehj Series workshops often pause at this slide:

Here are a few things to reflect on:

From the Sehj Series Workshop 1 Facilitator Guide:

“Sikhi does not attribute gendered assumptions. Our society imposes those.

- Sikhi does ask us to take control of all of our natural human instincts (whether anger, or greed, and sexual desire) and to engage in moderation, and with full introspection and intention.

- The Sikh Rehat Maryada, literally “code of conduct” (a document prepared over 20 years and formalized in the 1940s, outlines Sikh practices including birth and naming a child, marriage, death, etc) asks every Sikh to refrain from sexual relations outside of marriage. Consider what value or relevance this holds for you personally (on your own unique spiritual journey).

- Society and media may largely present sex as something all couples do, often spontaneously or very early in a relationship. However, the intimate acts of sex can quickly change the dynamics of a relationship.

- Have you had a chance to think about and reflect on your personal values and boundaries with intimacy?

- Some might want a deep emotional connection with their partner before having sex; some might prefer to wait until committing via marriage; and some might be ok with sex after just a few dates.

- Being a Sikh also teaches us to be sovereign. Our sovereignty extends to our right to not be forced into anything, including our right to consensual physically intimate interactions.”

Vaisakhi is a reminder of the basics. Of loving the Guru enough to sacrifice. Of sacrificing one’s privilege for the larger spiritual family. Of the importance of chosen family. Of each one of our Guru-given sovereignty that cannot be “shamed” or sullied by abuse, that is innate and indestructible, that is the inner power that will keep us standing strong even when we are that girl “everyone is talking about.”

Resources

RAINN: National Sexual Assault Hotline

800.656.HOPE (4673) 24-hour Crisis line

Live chat (https://hotline.rainn.org/online)

Sikh Family Center National Helpline

866.SFC.SEWA | 866.732.7392 | https://sikhfamilycenter.org/

Free, private, bilingual Punjabi-English, non-emergency support line

contact@sikhfamilycenter.org

Technology Safety

https://www.techsafety.org/– info and resources for safety

About Mallika Kaur

Mallika Kaur is a lawyer and writer who focuses on human rights with a specialization in gender and minority issues. Kaur has worked with victim-survivors of gendered violence for two decades, including as an emergency room crisis counselor, expert witness on intimate partner violence and sexual violence, researcher, and attorney. In South Asia, Kaur has worked on a range of issues including farmer suicides, female feticide, and transitional and transformative justice. In the United States, she has worked on issues of post-9/11 violence, policing practices, political asylum, and racial discrimination. She’s practiced family law in California including as counsel at ADZ Law, a San Francisco Bay Area family law and victims’ rights firm.

Kaur received her Master in Public Policy from the Kennedy School at Harvard and JD from UC Berkeley Law School, where she currently teaches skills-based and experiential social justice classes. Kaur writes regularly for online and print media as well as academic publications; her work has been published in Foreign Policy, Washington Post, Ms. Magazine, and California Law Review, among others. She regularly trains lawyers as well as non-lawyers on cultural humility, elimination of bias, and negotiating trauma.

Mallika is a co-founder and Acting Executive Director of Sikh Family Center, the only Sikh American organization focused on gender-based violence. Working with local civil society, academic institutions, advocacy organizations, and government agencies, she combines research, advocacy, scholarship, and the law as an approach towards sustainable change.

Kaur is the author of the book Faith, Gender, and Activism in the Punjab Conflict: The Wheat Fields Still Whisper (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019). She believes what happens inside a home is intimately connected to what happens inside a community as a whole: since struggles are interconnected, commitment to justice must never be selective.

1 Comment

Anonymous

01/14/2023 at 12:05 pmI want to know one thing

Being a gurmukh, when planning for a child

How to indulge in coitus. I mean the maryada.

I want to indulge in the act with focus on just to procreate. Maryada is of utmost importance to me.

also my spouse, she is very strict about maryada and all.

Things What i can think of while doing the act that keeps the act in maryada are

1. Lights off

2. Keeping maximum clothes on while doing the act and removing only those which are necessary to do the act. (like when we pee)

(also this point is must according to my wife and i totally agree with her )

3. Covering both of us under bedsheets.

Are these enough??? If i do it this way, will it be under maryada.

I hope so.

If anything more is required please do tell me.

Reply soon please.