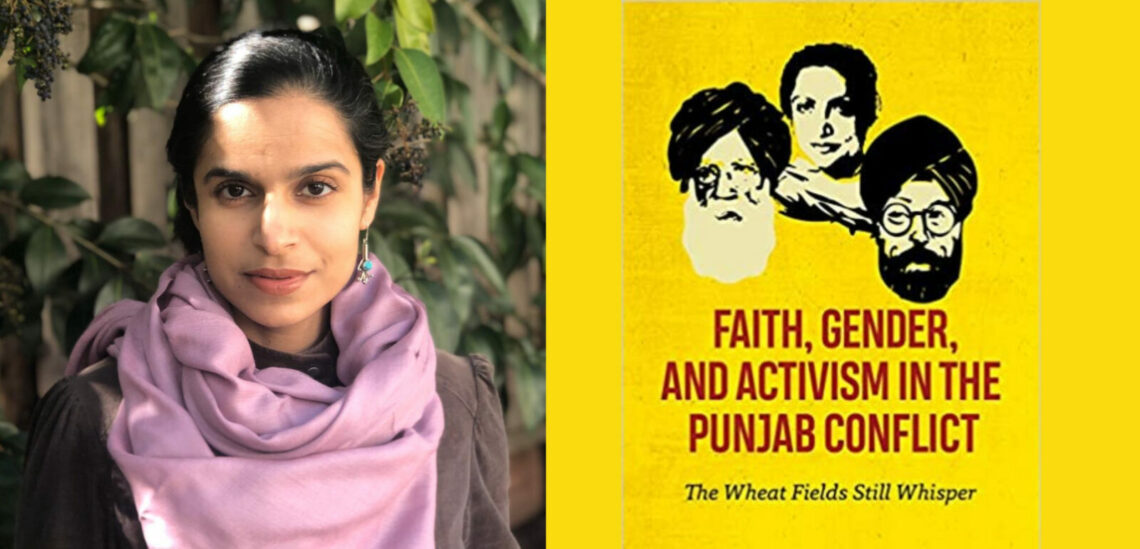

Author Mallika Kaur joins Kaur Life Editor-in-Chief Lakhpreet Kaur to discuss her new book Faith, Gender, & Activism in the Punjab Conflict: The Wheat Fields Still Whisper.

About the Book

Punjab was the arena of one of the first major armed conflicts of post-colonial India. During its deadliest decade 1984-1994, as many as 250,000 people were killed. This book makes an urgent intervention in the history of the conflict, which to date has been characterized by a fixation on sensational violence—or ignored altogether. Mallika Kaur unearths countless stories of those who struggled to uphold basic human rights. She employs as vehicles of storytelling the life stories of three extraordinary people who found themselves at the center of Punjab’s hazardous human rights movement: Baljit Kaur, who armed herself with a video camera to record essential evidence of the conflict; Justice Ajit Singh Bains, who became a beloved “people’s judge”; and Inderjit Singh Jaijee, who returned to Punjab to document abuses even as other elites were fleeing. These three as joined by countless others as each Chapter delves into a case seminal to Punjab’s conflict story. Braiding oral histories, community history going back to 1839, personal snapshots, and primary documents recovered from at-risk archives, Kaur shows that when entire conflicts are marginalized, we miss essential stories: stories of faith, feminist action, and the power of citizen-activists.

Trigger warnings

They will be mentioning extra judicial killings, rape, murder, violence and sexual assault.

Part 1

- What started this journey for you? Was there a mission you had set upon?

- Why do you feel that understanding some of those seemingly pedestrian stories or viewpoints are important to our collective consciousness?

- Was there anything surprising or interesting that popped up that you weren’t really expecting?

- Do you feel like your Sikh background or you being a Sikh woman informed your approach to this whole project?

- When you’re feeling down, how do you keep going and maintain perspective?

- Why do you suppose women’s stories are left out?

Part 2

- How did different women reject traditional feminie roles/behaviors/expectations vs embrace them as tactics in the struggle?

- Do you have any thoughts on what nuances we should consider when we envision a future of the Sikh Panth?

- What is your advice for modern day Sikh citizen activists who are aspiring to do similar work that you’re doing?

Excerpts from the Interview

Q: What drove the book?

A: [A]s the daughters of Guru Nanak Sahib, we get to ask whatever we want. This is a really empowering idea that’s at the core of our faith, and I always carry that with me. […] The dominant driving force for this book is that I had so many questions, both for myself, and questions I heard from friends and colleagues, even those mired in work around the conflict and the traumas it’s caused. There were just so many questions that felt they never got a fair set of answers, or were not even acknowledged as questions because they were not asked by such-and-such academic or so-so-funded grant. The questions people really have… that we had as kids, and our kids are going to have [ . . .] And the “Where are the women?” question is a dominant question for many of us.

Q: Do you feel like your Sikh background or you being a Sikh woman informed your approach to this whole project?

A: As much as we might talk about code-switching and all of that, I don’t think I ever leave these two intersecting identities at home… I’ve never felt my identity as an impediment to asking questions… Talking to the Sikhs I talked with in this book… Chardi Kalaa is very important [ . . .] The ascendent spirit thing we talk about is a process, it’s a commitment, and it’s not just a permanent state of being that will never ebb and flow. And that too, in the journey of this book, was very important.

Q: Why do you suppose Sikh women’s stories are sidelined?

A: We have for too long been comfortable with the idea that certain spaces are men’s spaces, and those are often the spaces where political activity happens.

In general, you might notice that during dinner parties or family gatherings, women gather in the kitchen and around the children, and the men are traditionally in the living rooms, having their discussions, not being disturbed [. . .] The women are cooking, serving, and taking care of the kids. Or in Gurdwara, who is the first person who usually rushes out when the kid has a tantrum? It’s usually the mom who then ends up missing on the kathaa, vichaar, announcements or discussions. We’ve been so comfortable with men not carrying basic labor in the domestic sphere, that we’ve left women out of very important conversations [. . .]

The same interactions we see playing out in the community, were playing out just that way before, a few decades ago. So during the conflict, women were managing their homes, managing all the trips to the attorneys, to the police stations, while their husbands were arrested, detained, tortured, killed. Yet, the people talking about those cases, a lot of human rights defenders even, and definitely the political leaders, are men, and spoke about the men.

Still we will say “ਸ਼ਹੀਦ ਸਿੰਘਾਂ” (Singh Shaheeds), and we will not say ਸਿੰਘਣੀਘਾਂ (Singhniyaan)… Often, people’s shorthand for Sikh activists of that time or people killed over that time will be “Singh.” Will only use that collective term. And it matters. It matters that we have Singhniyaan in our ardaas… In our everyday conversation even, we can’t leave that out.

Q: Do you have any thoughts on what nuances we should consider when we envision a future of the Sikh Panth? Growing up, I was presented with a machismo framing of Sikhi emphasising Singhs as lions. There was a glorification of violence and it didn’t seem holistic or embracing of all of the things that Sikhi has to offer, especially the diverse range of genders. So, I was wondering if you had any thoughts on what nuances we should consider when we envision a future of the Sikh Panth.

A: In a lot of ways, there is this machismo, hyper-masculine way of speaking about Sikh strength. Which is ironic because if one really goes back to the lives of and writings of the Gurus … and Gurbani, it is so poetic, beautiful, so emotional, that it’s hard to imagine that people negate that, and just focus on the soldier side of things. And even on the soldier side of things, forget that violence, or using or returning violence really has been an option that’s put out for us when all else fails. But there is so much that happens before. The fact that Guru Nanak Sahib was imprisoned when he called out Bhabar. Those are things we sometimes forget, about what civil disobedience look like, not just during the Guru period, but throughout the colonial period, through the 70s, into the 80s… [and] women were very much part of that resistance as well.

Women in the armed struggle

Some women were part of the armed struggle as well, which I talk about and problematize in the book. Looking at some of the stories that we have available of female combatants and in how their stories have been told, I noticed that there’s a masculinity ascribed to them, “They became like the men”.

When people think about Mai Bahgo, it’s like, “She left all the women and the chooriyan (ਚੂੜੀਆਂ) (bangles) at home, and then she became like the men.” Even this whole concept about, “sitting around wearing chooriyan” is a messed up cultural notion. Like, you can wear chooriyan and still be a revolutionary, there’s nothing contradictory there. But we’ve ingrained these ideas of what’s male or soldier-like.

Different forms of strength

So, when I think about a future vision of the Panth, I think we do need to celebrate strength in different forms. The definition of strength needs to be broadened and then celebrated. For instance, strength might be the strength of somebody who stands up against sexual violence in their own home. It might be of somebody who, no matter what, takes a stand for a survivor. It might be somebody who physically puts their bodies between somebody who’s being violent and the person who’s receiving the blows. It might be the strength of the pen, for a journalist. It might be forsaking how many Twitter followers you have and writing something that’s against the grain!

I think celebrating that type of strength or rebellion in a broader sense, will not only liberate women but it will liberate our men too. People who identify as male have to put aside so much of their emotion, and so much of their full humanity, just to perform masculinity.

Q: What is your advice for modern day Sikh citizen activists who are aspiring to do similar work that you’re doing?

- Go talk to other people, especially those who’ve experienced these things or times… And experience doesn’t have to be that they themselves were imprisoned, but that they lived through the 80s, the 90s… Just talking can help us learn a lot, even about how much we don’t know!

- Actually reading history […] In the book, I’ve deliberately, like a gutt, woven two different timelines 1839 to 1984 and 1995 to 1984. Survivors’ stories from that time are not linear, they often go back and forth. I hope as readers, people do pause and think, I have more questions about this time And that there are more books. So in terms of advice, read more, talk more, and then write more ….from our recent history there are still so many untold, unexplored, uncelebrated stories.

Buy Your Copy

From the publisher, Springer.

From Amazon.

From Alibris

From your local bookshop.

No Comments