By Tavleen Kaur

Trigger warning: This article discusses domestic violence, substance abuse, marital rape, suicide, hate violence, sexual harrasment, self-harm, and depression.

Before you continue, be sure to read Part One first.

Here, in Part Two, Tavleen Kaur continues her conversation with Sohji Kaur as they try to asses the current health of the Sikh community.

…has faced gendered roles and expectations // has benefitted from gendered roles and expectations

Sojhi Kaur distinctly remembers an incident regarding this. One time she and her husband were in their home kitchen. The two of them were talking while she was cooking dinner for them. At that moment, her mother-in-law told her son, Sojhi Kaur’s husband, to go in the living room, saying that “men don’t look good in the kitchen” (i.e. it’s not their place). He stood there; he didn’t leave, but he was silent. His silence upset Sojhi Kaur even more. In that moment, and hundreds of other moments, her husband benefitted from gendered roles and expectations, even if he didn’t prescribe to them. She later told him that his silence set a terrible example for their children. This is not how they wanted to raise their children. She racked her brain for days when these kinds of incidents happened. Eventually it came down to understanding that her mother-in-law is “old fashioned” (though this rationale is silly, because it erroneously assumes that there were no “woke” women and resistance movements among the older generations). Yet, it’s the only rationale that made an ounce of sense. Her mother-in-law was old fashioned. Her entire life was spent in servitude, because that’s what she had seen her mother and grandmother spend their lives as. She and the women before her were weighed down with gendered expectations and roles. They weren’t seen as individuals. They were seen as labels: wife, mother, daughter, daughter-in-law. They weren’t asked how they were feeling, what they wanted, what they liked and disliked. Their opinions weren’t asked, nor did they matter to others around them. Their decisions were made for them. Sojhi Kaur has spent most of her adult life fighting these battles in and outside the home. Sometimes she doesn’t have the physical or psychological energy to fight them. She remembers her friend’s daughter showing her the “you should have asked” comic about the emotional labor women have to do.

…faces class- and/or caste-based discrimination or persecution

Sojhi Kaur comes from a working class background, though her caste background of “jatt” accords her some social privileges that others who are deemed “lower class” do not have. Due to her class status, she is hyperaware of her visions and goals. Not everything is achievable, and life dreams have to be realistic. She has accepted this fact. One of Sojhi Kaur’s relatives, a jatt female, is married to a Punjabi Sikh man hailing from the Dalit community. Because these individuals defied social expectations and married outside the caste subgroups their families belong to, they were cut off by family on both sides. Sojhi Kaur can’t understand this one. What is so terrible about shunning an oppressive system? The two individuals this anecdote is about have lived a lovely life together, and they’ve never looked back.

…does not have health insurance

Thankfully, Sojhi Kaur has not had to face health insecurity. She has spent most of her life in England, where the social welfare system (for now) has universal healthcare. She feels for her relatives in the U.S., however. She has a distant cousin there who is one of millions of people in that country who cannot afford healthcare. The cousin has some chronic health issues, and due to this, they either have to live in pain or pay extortionate amounts of money to get even basic care. Because the U.S. healthcare system operates on a business model, so many people cannot afford visits to the doctor’s office and prescriptions. Unlike their counterparts with health insurance, people like her cousin approach their deaths twice as fast—first due to their medical conditions, and secondly due to unaffordable healthcare.

…has been a victim of hate violence

Sojhi Kaur’s relatives in various parts of the world live in this fear. On Punjabi TV channels, she often hears about hate violence cases in Europe, North America, and Oceania. She noticed that the common denominator among various cases of hate violence was Islamophobia directed at Muslims, Arabs, and everyone “suspected” of being so. She wondered what Sikh diaspora communities’ response to hate violence would be if it weren’t only so Sikh-centric. Afterall, hate violence is a much, much larger issue bred both by the ongoing war on “terror” and modern states’ historical legacies of racism.

…needs mental health help // has attempted self-harm

For a long time, Sojhi Kaur didn’t understand what mental health was all about. Everyone feels a little down, disconnected, and not like themselves. What was the big deal? The gravity of not having adequate mental health awareness and wellbeing access didn’t hit home for her until she heard about an apparent murder-suicide that took place in Atlanta, Georgia in 2013. A Punjabi Sikh couple and their two children, ages 12 and 5, were found dead in their apartment. The news shook the entire Sikh diaspora. It was at this time that Sojhi Kaur thought in retrospect of so many other cases of murder and suicide in the South Asian community in England alone. Sojhi Kaur knows several cases of suicide from within her own social network. What must someone be going through to take their own life, or that of their loved ones? What if there were support and help along these individuals’ journeys? Sometimes Sojhi Kaur wishes she were 30 years younger so she could do community work. Sometimes she wishes she could go back 30 years and understood mental health then like she does now. She’s grateful that today’s naujavan (youth) have taken up initiatives on mental health (and see substance addiction as a mental health issue).

…would like to pursue higher education but can’t because of cost, legal status, family situation, etc.

Sojhi Kaur’s niece in the U.S. has much to say about this. She wants to pursue a Master’s but can’t due to the high cost of education, her financial situation, and family obligations. Stereotypes on Asian Americans, however, cast her as an exemplary model minority. However, she vehemently opposes narrativization of Asian Americans as a “model minority.” She dislikes that concept with a passion. A simplistic understanding of Asian Americans (or Asian Canadians and Asian Brits) as a “model minority” may sound congratulatory and might even be a sought-after label by Asian Americans themselves. However, a more critical look at where and how this concept originated and whom it excludes shows just how pernicious it is. Sojhi Kaur’s niece has learned much about this. Briefly summarized, though, Sojhi Kaur now understands that the “model minority” myth pits minorities against one another. It views the apparent “successes” of Asian Americans in contrast to the apparent “failures” of Black Americans, thus totally eliminating the roles of slavery and Jim Crow in creating inequity and puts the onus to “fix” these institutionally-created disparities back onto the people. This myth also glosses over large populations of Asian Americans struggling with finances, legal status, and educational opportunities. Further, it groups all Asian Americans as one large group, ignoring the particulars of disparate communities of Asian Americans. Sojhi Kaur’s niece is one among thousands of others who do not fit the stereotype of financially well-endowed second-generation Asian Americans.

…is Punjabi Sikh and undocumented

Sojhi Kaur and her family are survivors of the 1947 Partition of Punjab. The mass exodus reminds Sojhi Kaur of a contemporary exodus of a different sort—Punjabi youth lured into going abroad without proper documentation, with dangerous journeys facilitated by “agents” who charge these youth extortionate amounts of money. Countering normative assumptions on where undocumented migrants in the United States hail from, recent data shows that the fastest-growing population of undocumented people comes from India (followed by China, the Phillippines, and Korea, respectively). Immigrant detention centers in the U.S. have large numbers of Punjabi Sikh (mostly men) detained individuals. Data also shows that, beyond detention, 1 in 7 Asians in the U.S. is undocumented. Sojhi Kaur can’t help but think about the dire economic conditions and political persecution that leads Punjabis to embark upon dangerous journeys in hopes of making it to the U.S. Sojhi Kaur remembers the heartbreaking story of 6-year-old Gurpreet Kaur who died of a heat stroke in triple-digit heat in the Arizona desert in 2019. Reflecting on all this, Sojhi Kaur is at a loss for words. She feels survivor’s guilt from 1947 to 2020.

…is a racist

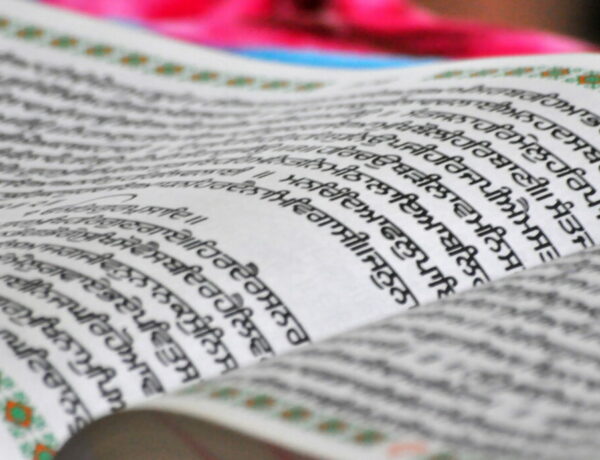

Maanas ki jaat sabai ekai pehchaanbo

Recognize all of humanity as one. -Guru Gobind Singh

Sojhi Kaur wonders how Sikh folk can harbor anti-Blackness, Islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia, colorism, casteism, classism, and various other kinds of prejudices and discrimination. Sikhs have a history of being persecuted, whether historically in South Asia or in the present day in all corners of the world, from Afghanistan to Germany. How does an oppressed community become the oppressor? Sojhi Kaur’s blood boils when she hears British Punjabis (of all generations, mind you) use “Paki” as an Islamophobic racial slur. Have Sikhs forgotten that Guru Nanak’s closest companion, Bhai Mardana, was a Muslim? One time Sojhi Kaur was visiting family in the U.S., and one night, one of the relatives she was staying with remarked that they forgot to lock the front door before retiring for the night. As this relative went to lock the front door, they remarked that while the neighborhood they’re in is relatively “safe” (code for upper middle class, mostly white and rich Brown folks), “you never know when a kala (person who is Black) might break in.” Yes, those were their exact words. Why did this relative equate Blackness with criminality? She wonders why Islamophobic Punjabi Sikhs don’t realize that the white supremacist gaze sees our community as exactly what we try to distance ourselves from: “Paki,” “suspect,” and “terrorist.” As former-white supremacist Arno Michaelis says himself, white supremacist groups are “anti-foreigner, anti-black, anti-gay, anti-Semitic, anti-anyone-who- didn’t-fit-into-our-crude-worldview.” Sojhi Kaur wants our community to realize that burqas, hijabs, yarmulkes, turbans, beards, patkas, and scarves are not the issue; white supremacy is. Racist Punjabi Sikhs reproduce the very hate and bigotry that they themselves are victims of.

Who is Sojhi Kaur?

The reasons Sojhi Kaur crossed off every box on the Bingo sheet is somewhat unremarkable, in that many thousands like her from the Punjabi Sikh community, especially women, can identify with the content of the Bingo sheet. The unremarkability of this process, however, does not take away from the gravity of it. In fact, it further emphasizes it. How can it be that everyone who’s filled out the Bingo sheet crossed off so many boxes?

I want to tell you more about Sojhi Kaur.

I’m Sojhi Kaur.

You’re Sojhi Kaur.

We’re Sojhi Kaur.

Sojhi Kaur is a personification of the global Sikh Panth.

Sojhi Kaur’s anecdotes are a compilation of real stories and real people. If we view Sojhi Kaur as an individual, it’s not difficult to see that she’s had a hard life, and that her community, like any community, is full of rifts.

Many thousands like her in the global Sikh Panth live with deep, intergenerational trauma, and the psychosocial effects of abusive partners/relatives, racism, misogyny, patriarchy, homophobia, anxiety, discrimination…the list goes on.

With this in mind, I ask you, how is the mental state of the Panth? Is she doing well? What kinds of help does she need? How can she break these various cycles of silence and violence? How can she break free of systemic and institutional shackles so that she’s not confined to what she’s consigned to?

As “Sojhi Kaur” understands, the answers to these questions boil down to Nirbhao and Nirvair—love fearlessly, live fearlessly. If we ever feel disconnected from Gurbani, remembering even just this part from the Mool Mantar can feel grounding.

May the Sojhi Kaur that each of us embodies see Ik Oankaar in all of Waheguru’s creation, including our own selves. We can only love fearlessly and live fearlessly if we love ourselves first. By “self-love,” I mean a kind of radical self-love that compels us to face our deepest and darkest blindspots, hatred, silence, complicity, complacency, stereotypes, and misunderstandings that keep us from seeing Waheguru in others.

Next Steps

There is a lot going on in this article, and that’s entirely intentional. I wanted to lay bare these issues, not to paralyze you or myself with the immense gravity of these topics. Rather, I’ve written this article so that we can at least be aware or be reminded of all that ails us. Then, to start with, perhaps we can each take at least one issue from the bingo sheet and really understand its history and nuances, and commit to (un)learning more about it.

Desiring a healthier Panth has to start at an individual level, and likewise, healthy individuality has to be cultivated in relation to our broader communities. In the words of Indigenous Murri activist and artist Lilla Watson, “If you’ve come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” The purpose of this article is not to make individual readers think they alone can “fix” these issues. Rather, our healing, ergo the Panth’s healing, can only happen when we each see not only how we perpetuate these issues but also unlearn the systems that got us to this point in the first place.

What does co-bound liberation look like?

If you’re looking for that one issue you can get involved with to help heal the panth, check out these organizations and initiatives that are trying to change the tide.

About Tavleen Kaur

Tavleen Kaur (she/her/hers) holds a PhD in Visual Studies from the University of California, Irvine. Her past work examines how the bodies and buildings of contemporary diasporic Sikh communities become targets of racialized hate violence. Her current research is on the formation of diasporas of undocumented Sikhs in Central and South America over the last few decades. She is passionate about architectural history and theory, and community development and mobilization. She particularly enjoys smashing the heteropatriarchy and conceptualizing a life outside the capitalist-militarist realities of the present day. Guru Nanak is her constant inspiration to pursue these ideas and projects.

No Comments