By Tavleen Kaur

Trigger warning: This article discusses domestic violence, substance abuse, marital rape, suicide, hate violence, sexual harrasment, self-harm, and depression.

How is the Sikh panth doing? What is the current health of our community? Tavleen Kaur tries to answer these questions by talking to Sojhi Kaur. Together they explore the challenges the panth faces and what we can do to address them.

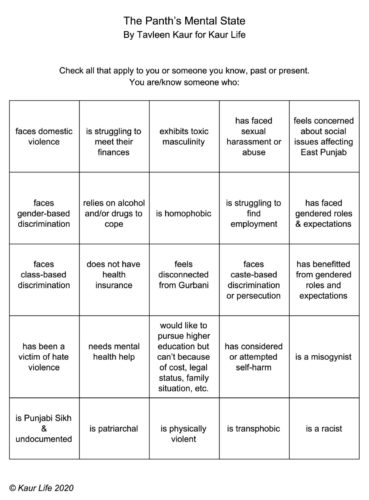

Let’s Play Bingo

Thank you for making time to read this article. I’m sorry to share that this is not a “feel good” article; rather, it’s simply one to feel. This is an interactive read. Before you scroll further down, please take a minute to fill out this Bingo sheet.

Let’s see how you fared compared to Sojhi Kaur.

Meet Sojhi Kaur

She’s a Sikh woman in her 60s who lived in India until her mid-20s, after which she moved to England to live with her husband. Sojhi Kaur filled out this bingo sheet, and perhaps unsurprisingly, she ticked off every single box. Every single one. What could she have possibly been through, and what kind of social network must she have that she identified with every box on the bingo sheet? She shares anecdotes explaining why every box is relatable for her.

…faces domestic violence // is physically violent

Sojhi Kaur feels especially woeful about this box. Her best friend is a survivor of domestic violence. Sojhi Kaur’s best friend felt hapless and stayed in an abusive marriage for more than a decade because, like Sojhi Kaur, she had moved to an entirely new country after getting married. Her abusive husband used immigration as leverage, and on top of that, the two of them had a baby girl. The woman had no other family in England, and she didn’t feel comfortable returning back to Punjab due to cultural stigma her parents would likely feel on account of their married daughter living in her maiden home. The woman felt stuck in every way. For these reasons, she endured many years of abuse. When Sojhi Kaur got wind of this situation, she helped her friend locate community resources to escape that toxic, violent environment.

…is struggling to meet their finances

This is Sojhi Kaur’s own life story. Like many women of her background and circumstances in England, she worked in a sewing factory. It was hard work with little pay. Her husband worked an unreliable labor job. The two of them lived on a shoestring budget, struggling to make ends meet for themselves and their two children. She has little savings and is unsure what life holds for her as she approaches her 70s.

…exhibits toxic masculinity

Sojhi Kaur says she has lost count on this one. She knows so many men in her community who exhibit toxic masculinity. In fact, her best friend’s abusive husband is a case in point. The names of her husband and his father, and of her own father come to her mind upon seeing this box on the bingo sheet. She recalls how these men would curse at their wives, misplace their anger on them, refuse to talk about their feelings, walk out in the midst of an argument rather than address the issue at hand, and fail to think about the repercussions of their actions. She wishes men could understand how hurtful “casual sexism” is and how such remarks have an adverse effect on men’s own psyches. She has seen and experienced so much toxic masculinity that she doubts she’s ever come across healthy masculinity, the kind in which men freely express, cry, create, be tender and vulnerable, and feel attuned.

…has faced sexual harassment or abuse

Sojhi Kaur goes quiet on this one. After a few minutes, she speaks up, though barely audible. She is trying to hold back tears. Aaho, she says choked up. Her only two words following this are, meri bhain (my sister). Many moons ago, Sojhi Kaur had briefly shared that her sister in Punjab had faced marital rape repeatedly. Menu puchheya vi nahi (x didn’t even ask me), her sister said. Her sister knew that what she had been put through was wrong, yet she couldn’t express the lack of consent (and thus, rape) in words that her family and relatives would find credible. Her sister’s ears bled each time she was told, “But he’s your husband! It’s your duty!” These comments come from a society whose country believes that criminalizing marital rape means “men will suffer.” Sojhi Kaur shakes her head recalling this.

…feels concerned about social issues affecting East Punjab

When Sojhi Kaur’s friends from gurdwara came back from a two-week stay in East Punjab, they described how different everything seemed from their previous trips. The “marbleization” of gurdwaras was off-putting, as was seeing a “theka” (liquor stand) every few miles. Hearing about the latter made Sojhi Kaur think about just how widespread the social and medical issue alcoholism is. Her friends also talked about how they and their hosts in Punjab had to be extra vigilant about the water they drank, even for brushing their teeth. Using filtered or bottled water is a privilege, leaving many others to use water that has become toxic due to use of carcinogenic pesticides that seep into the (rapidly depleting) groundwater. The beautiful green fields are a dangerous facade, concealing the horrors of extrajudicial killings of Sikhs by the Punjab police and thousands of suicides by farmers. Sojhi Kaur’s memory of Punjab teeters between it being the sweet homeland it was and a zone of social warfare that it is.

…faces gender-based discrimination // is a misogynist // is patriarchal

She sighs deeply at seeing this box on the Bingo sheet. Her children told her about the Pink Ladoo Project, a campaign that fights sexism and taboos surrounding the birth of girls. When some of Sojhi Kaur’s friends had baby girls, she could not believe the snarky comments and disapproval some of the relatives of those new mothers received. She has even heard of cases of Sikh women being forced to abort female fetuses or witness (or be coerced into committing) infanticide of baby girls. This historical and present social ill is the intersection of gender-based discrimination, misoygyny, and patriarchy. She is moved to tears every time she remembers Bibi Parkash Kaur and her institution, Unique Home in Jalandhar. The home is a haven for abandoned baby girls. Sojhi Kaur’s heart breaks when she thinks about the lost lives of born and unborn baby girls.

…relies on alcohol and/or drugs to cope

This one that really gets under Sojhi Kaur’s skin. Here she’s thinking of her father-in-law’s excessive drinking and the physical and verbal abuse that followed. Attempting to understand his addiction as a mental health issue, she tried really hard to be empathetic when he was still alive, though she could not wrap her head around how someone could be heartless and so careless about their own health, ergo be so blind to how their carelessness means constant worry for everyone around them. Sojhi Kaur read in the news that nearly one-third of Sikh community members in the U.K. say they have a family member who abuses alcohol. In other words, nearly one in every three Punjabi Sikhs in England have at least one family member who abuses alcohol. Sojhi Kaur often thinks about how this and other common health issues in our community—such as heart disease and diabetes—intersect to create a bleak, dangerous reality. She finds some comfort in knowing that language-accessible resources are now available to understand, cope with, and support individuals with alcohol use disorder.

…is homophobic // is transphobic

Sojhi Kaur used to have a hard time with this one. Until one of her fellow Punjabi Sikh friends from the factory shared that her daughter came out as a lesbian, Sojhi Kaur hadn’t really thought much about gender, sexuality, or queerness. Sojhi Kaur wondered what she would say and how she would react if one of her own children came out as LGBTQA+. Her immediate thought is of gratitude, that after all her family has been through, that her children feel comfortable confiding in her. Her friend was quite upset, saying that her daughter’s “ways” were “wrong,” and that her queerness reflected her parents’ failure. Sojhi Kaur knew that was a hurtful response, and while she didn’t agree with their views, she understood where the parents were coming from. After a lengthy process, all the family members have now come to terms with the fact that one member among them has transgressed “rules,” but that that’s how it shall be. This was the more “amicable” of instances. Sojhi Kaur knows about another few that were not so. Those comings out ended with total loss of contact among the family members, disownment, and depression.

In the past, sometimes she, too, found herself influenced by cultural baggage of “morality” and “izzat.” In those moments, she reflected on how most of us live our lives according to constructs. When someone challenges these constructs to pursue their own sense of self and identity, we look down upon them, maybe because their bravery makes us reflect on our own fears. Sojhi Kaur finds comfort in remembering how many “rules” and “traditions” the Gurus challenged and condemned. For one of the most poignant perspectives on homophobia among Brown communities, Sojhi Kaur cites Dr. Nayan Shah, Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity. Shah writes, “In political debates about who benefits from the extension of marriage licensing to gay and lesbian couples in both Canada and the United States, Sikh-Canadian religious leaders and black evangelical preachers condemned homosexuality as a ‘white disease’ and feared the acceptance of gay and lesbian couples would contaminate their racial and religious minority communities. The urge to make gender and sexual diversity invisible to their own communities is a survival strategy to deflect decades of white suspicion and state persecution that insisted that Asian, Black, and Latino communities were the source of sexual perversity.” She realizes our community has a lot to unpack and unlearn as we educate ourselves more.

Sojhi Kaur reflects on how Gurbani reminds us that the essence of all of Waheguru’s creation is jot (light). Being judgmental and hateful keeps us from seeing, believing, and feeling that jot dispersed among everyone and everything. Sojhi Kaur finds comfort and peace in the idea that once we see that jot in others and ourselves, no one seems an enemy or stranger:

ਬਿਸਰਿ ਗਈ ਸਭ ਤਾਤਿ ਪਰਾਈ ॥

ਜਬ ਤੇ ਸਾਧਸੰਗਤਿ ਮੋਹਿ ਪਾਈ ॥੧॥ ਰਹਾਉ ॥

ਨਾ ਕੋ ਬੈਰੀ ਨਹੀ ਬਿਗਾਨਾ ਸਗਲ ਸੰਗਿ ਹਮ ਕਉ ਬਨਿ ਆਈ ॥੧॥

ਜੋ ਪ੍ਰਭ ਕੀਨੋ ਸੋ ਭਲ ਮਾਨਿਓ ਏਹ ਸੁਮਤਿ ਸਾਧੂ ਤੇ ਪਾਈ ॥੨॥

ਸਭ ਮਹਿ ਰਵਿ ਰਹਿਆ ਪ੍ਰਭੁ ਏਕੈ ਪੇਖਿ ਪੇਖਿ ਨਾਨਕ ਬਿਗਸਾਈ ॥੩॥੮॥

…is struggling to find employment

Sojhi Kaur herself and so many of her immigrant friends can relate to this one. She’s experienced first hand that networking plays a bigger role in securing employment than even merit. When Sojhi Kaur first moved from Punjab to England, she had a hard time finding work in any sector, particularly her field, education. She would see people less qualified than her get the jobs she was after. She quickly internalized the label of “unemployed,” and disliked that many equated “unemployed” with “incapable.” She wondered why her worth was connected to productivity, but that seemed to be the way of the world. Through word of mouth, Sojhi Kaur eventually landed employment in a sewing factory, a job she stayed with her entire working career and was never once offered a promotion. People don’t see laborers like her as having goals and aspirations. Her boss treated each of the factory employees as a cog in the wheel. Due to her experiences, she has so much respect for laborers. The whole world is now realizing what Sojhi Kaur has known all along—that the entire global economy depends on “low-skilled” labor, which has now conveniently been relabeled as a force of “essential workers.”

Continue to part two…

About Tavleen Kaur

Tavleen Kaur (she/her/hers) holds a PhD in Visual Studies from the University of California, Irvine. Her past work examines how the bodies and buildings of contemporary diasporic Sikh communities become targets of racialized hate violence. Her current research is on the formation of diasporas of undocumented Sikhs in Central and South America over the last few decades. She is passionate about architectural history and theory, and community development and mobilization. She particularly enjoys smashing the heteropatriarchy and conceptualizing a life outside the capitalist-militarist realities of the present day. Guru Nanak is her constant inspiration to pursue these ideas and projects.

Photo by BOSS Sikhi Camp

No Comments