by Manvinder Kaur

I think we would be naïve to believe the answer is “no.” We could play the gate-keeping gymnastics of Sikh Twitter and fain that those who do drink alcohol are not real Sikhs or are bad Sikhs but that would not erase its reality.

When I’ve spoken to community members about why problems with alcohol exist in our communities, Punjabi culture is used as a scapegoat (and by association masculinity, Punjabi music, and intergenerational trauma, among others, come up). The assumption: Drinking alcohol is inherent to what it means to be Punjabi. But is it? It’s important to contextualize, historicize, and politicize where such a brushing off comes from.

Growing Up

I grew up in a household where alcohol consumption by males was normalized. At gatherings with other families, the uncles would splay out on the couches in the other living room and pour indiscriminate amounts of water into their whiskey while the aunties rolled out roti.

This created, what I could call, the landscape of my childhood, a space where I learned a lot about alcohol but also gender norms, relationships, and communication.

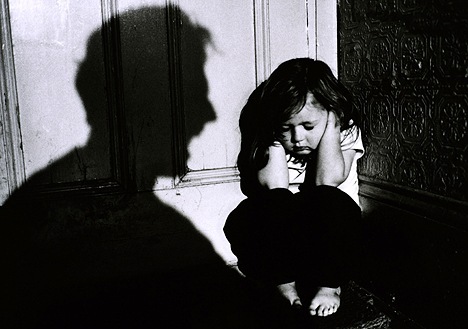

I would hide under my blanket at night, waiting for the yelling to subside or try to get in the middle of it when it wouldn’t. Sometimes I would hide my face in shame when they would make an absurd comment as we left a family friend’s house or I would feed the deep urge within me to escape and start drinking as well.

Eventually, we became accustomed to it and expected the behavior. Maybe some will see this as perpetuating or excusing problems with alcohol but I see it as more complex than that. I think I have simply found a different way of engaging with the problem that allows me to not be consumed by its impact and presence in my life.

Who am I outside of the impact alcohol has had on me?

A friend once described chardi kala as radical acceptance of your circumstances. After 26 years, I think I’ve slowly started on that journey.

When I see members of my family struggling, anger and annoyance bubble up. The same old routine to which I reply with an eye roll but later, many moments removed from the situation, I am able to see with compassion. I see someone who is struggling and has found a coping strategy that keeps them going.

Although I would argue that I’ve learned to cope with the idea that some individuals will never seek support, any time I’m around such situations, my childhood feelings come creeping back and all the empathy and radical acceptance is undone and is replaced with a deep disappointment and a hidden-away hatred.

I think James Baldwin describes it best in Giovanni’s Room where the main character is describing his father returning from an evening out: “I could tell by the sound and the rhythm that he was a little drunk and I remember that at that moment a certain disappointment, an unprecedented sorrow entered into me. I had seen him drunk many times and had never felt this way – on the contrary, my father sometimes had great charm when he was drunk – but that night I suddenly felt that there was something in it, in him, to be despised” (p. 13, 1956).

Researching Problems with Alcohol in Punjabi-Sikh communities

These experiences were also what pushed me to understand the root causes for why problems with alcohol exist in Punjabi-Sikh communities.

When I was doing my research, dukh daru sukh rog bhaiya (Guru Nanak Sahib, Ang 469), plagued me every time I went to write. It made absolutely no sense to me and when I finally thought I had grasped it, it was ripped out of my hands whenever I was asked to share my understanding.

In the Sikh Research Institute’s (SikhRI) interpretative transcreation, this line can be understood, as “suffering has become medicine, and happiness/comfort a disease.”

However, as we all know daru is how we colloquially refer to alcohol so in this vain, alcohol is suffering? Suffering has become alcohol? Suffering has become like alcohol? Suffering has come to feel similar to what it feels like to be intoxicated by alcohol?

As the salok continues, it is revealed that “in suffering the Creator is remembered.” In our (metaphorical) intoxication with our love of the Divine, within our suffering, the Creator is remembered.

Returning to the transcreation, we understand that this line is not referring to physical suffering but the multitude of spiritual ailments one may experience (e.g. psychological, mental, and emotional suffering). The Guru “tells us that suffering from these spiritual ailments can be the cure for the ailments themselves” and that too much pleasure or sense indulgence can become the “disease” because we are “comfortable or when we have been swallowed by those sense indulgences, there is not Longing for connection” with IkOankar. The suffering is actually “the cure because it allows us to reflect, it lifts us out of our indulgence and into introspection.”

However, this does not mean we dwell on the pain. In the next line there is a contextualizing where we can situate ourselves within the vastness of creation, where our pain is not “the biggest thing in the room” and there is something much bigger than we can understand.

I understand this line now as, “Suffering is where the growth occurs, where your relationship with IkOankar becomes stronger”. And if it is not IkOankar for you, then whatever you call that in your life which is unfathomable.

This understanding is of course contextualized within my own life experiences where race, class, caste, gender, and sexuality provide the landscape upon which my circumstances exist.

This also informs how I understand and contextualize my parent’s life experiences. For example, caste privilege allows my family (and all those who fall into the caste privilege/oppressor category) to define what Punjabi culture means and the ‘correct’ way to enact it and allows us to create the violent boundaries that force others out of this category unless they are willing to assimilate. Of course this must be contextualized within larger power structures of Hindu nationalism and white supremacy but this does not mean it should be forgotten.

Mental Health Resources

Looking outwards towards popular discourse within South Asian diaspora communities around mental health and addressing problems with alcohol, although there has been a growing urge to “normalize” conversations about mental health and create “culturally competent” resources for racialized communities, these resources continue to rely on and perpetuate colonial tropes that paint white communities as progressive and forward thinking and racialized communities as inherently and reprehensibly flawed and backwards. Many South Asian mental health social media accounts function from a deficit-based model, where there appears to be a clear monolithicizing and focus on childhood trauma that elicits social media attention.

Those interacting with these infographics of course see themselves, forcing a further homogenization of South Asian communities at large, fulfilling the colonial project of removing history, politics, power, and violence from the lives of racialized communities. It is not that what these pages are sharing is false, it is that what they share is often paternalistic when referring to immigrant parents or romanticizing white experiences.

When I read research about Punjabi communities written by white authors, it always feels unsettling. When I read quips about immigrant parents written by their children, it always feels unsettling.

A constant painting of immigrant parents as either people who do not know better and must be educated, villains, or mythical struggling immigrants, feeds into a power dynamic within which children are the holders of knowledge and have the power to define their parents without consulting them.

But how is this work decolonial (if it even seeks to be so)? How is it providing pathways to kind and compassionate conversations as opposed to creating graphics that decontextualize, villianize, and infantilize immigrant parents including those who struggle with problems with alcohol?

I recently had a conversation with a friend and they shared that they are currently grappling with understanding mental health through voice. That what they thought or assumed their mother needed was actually wrong and in reality, it was not a wild and free liberation but that they simply wanted their voices to be taken as true and responded to, speaking to varied understandings of what freedom can mean to different individuals.

Some individuals in my family have likely been drinking for over 40 years (I say likely because they still won’t tell me when they started or will snidely remark that they don’t drink) and I don’t think I will ever ask them to stop or seek help. This possibility is first and foremost a privilege. There is no biological dependence or any immediate health repercussions as of yet and the disturbances (read: violence) it causes in our day-to-day lives have now come to a minimal.

I think for me to advocate for my individuals in my family to seek help would be to advocate for them to confront memories and feelings that they have been suppressing for over 40 years. Memories and feelings that they do not want to confront and quite frankly memories and feelings that I am scared for them (and me) to confront.

Meeting My Family Where They Are

When I ask individuals in my family a question and they answer in a way that I would not answer it, I don’t take it as false. I inhabit their response and attempt to see how they see it: as truth.

Meeting people where they’re at and moving with them is essential in the healing journey. Breaking down hierarchies of who knows what is most correct allows for the two to be in dialogue with each other as opposed to against each other.

As Nikisha Khare and Nanky Rai share, through reflections from attendees at the Liberation Health Convergence, “oppressed communities have the capacity to provide their own health care,” and they don’t necessarily need “experts” or the power dynamics they represent. In building parallel structures of health, these communities “lessen their dependence on the institutions that brutalize [them]’”.

Resources:

If you or anyone you know may have a challenging relationship to alcohol please visit Asra: The Punjabi Alcohol Resource or email contact@asranow.ca for resources and information about addiction, harm reduction, withdrawal and more in English and Punjabi.

You can also check out AAS. AAS is a program that seeks to start conversations about problems with alcohol in our Punjabi and Sikh families and communities.

About Manvinder:

Manvinder Kaur Gill is a community-based researcher whose work is centered on religion, culture, and health. She holds a BSc. and a BA (hons.) from the University of Winnipeg. Her MA in religious studies from McMaster University aimed to understand the intersections of alcohol and Sikhi, particularly considering influences of colonialism, gender, and intergenerational trauma. She has held research fellowships at Delhi University and the University of Victoria. She is currently pursuing her Master of Social Work at the University of Toronto where she holds a research assistantship on a project titled “Border(ing) Practices: Systemic Racism, Immigration, and Child Welfare” and is completing a clinical and research-based internship at Women’s Health in Women’s Hands, a community health centre providing primary health care to Black Women and Women of Colour from Caribbean, African, Latin American, and South Asian communities in Toronto. Her work aims to reimagine colonial narratives and direct energy towards frameworks of love, sovereignty, and fostering spaces of co-learning. She is the co-founder of Asra: The Punjabi Alcohol Resource (asranow.ca), a youth-led grassroots initiative bringing her research into practice.

2 Comments

Anonymous

10/08/2021 at 11:54 amAlcohol can also be traced to Yogis. There are several shabds in gurbani that are around making alcohol. Of course, they are about making alcohol for aatma. But, those conversations were with Yogis who offered actual alcohol as aid in dhyan sadhna. You can infer from this that Yogis were alcoholics. Yogis were followed at large (still to some extent, i.e. Balak Nath) in Punjab. Punjabis took this habit from them – whether under spiritual context or not. This is not dissimilar to west taking alcohol from Jesus or, later, different saints.

At least, that’s my interpretation of whole Punjabis and alcoholism.

Anonymous

04/17/2024 at 10:38 amHi,

Thank you for the article (https://kaurlife.org/2021/08/05/do-sikhs-drink/).

It helps me understand the historical and personal issues with alcohol and Sikhs/Sikhism (and alchol/drugs/religions per-se).

It brings to mind my prsonal observations around ANY life-style and mindset that struggles with combining theistic-beleif/society/personal-existentialism, the three cannot exist simultaneouly without confict; the massed distractions and pressures to conform to peer-pressure and some ‘authoritarian ideal’ only serve to cloud the factors. This stress of wanting to believe three (or more) mutally exclusive things creates a conflict within both individuals and groups, and of itself any two excludes and contradicts the third.

Only by accepting that the reason any such conflict exists is that at least one of them is fundamentally flawed can anyone find a reasonable and realistic acceptance of self, and from that also acceptance of others without active conflict.

The idea/notion that alcohol/drugs/gambling etc are coping mechanisms or weaknesses is an error in itself. The coping mechanism, and therefore the stress is the idea/attempt to seamlessly and harmoniously blend three immiscible concepts.

Drinking alcohol or taking other drugs/actions, and then excusing behaviour/consequences because of it, is just an immature deflection from realising/admitting that personal/societal immaturity.

Alcohol/drugs/etc, in amounts/moderation within your own control, and being able to function in a reasonable manner, is a sign of your own stability and acceptance of reality, not a ‘coping-mechanism or weakness.

Any Theism/drugs/alcohol/distractions that result/excuse in immature actions/thoughts are the real ‘addictions/escapism’.

By just being a reasonable human-being; there is no need for the excuse/fantasies of ‘gods’/negative-distractions/fatasies/’drugs’ or other behaviour/beleifs that are actually just poor excuses for other inate manifestations for tribalism/weakness.

Peace.