by Harleen Kaur

“The Sikh identity is only for men.”

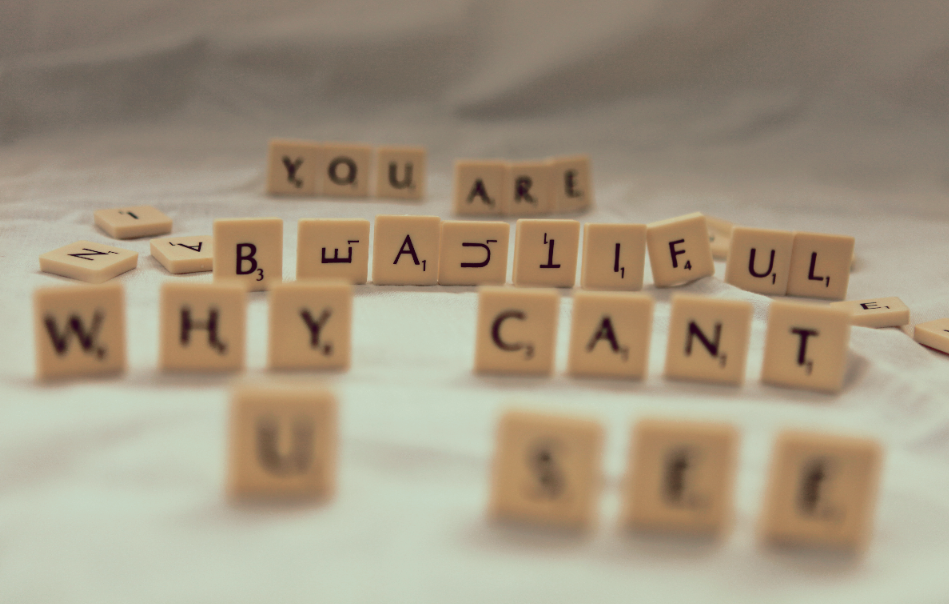

I sat, stunned, unsure of how to respond. The statement had entered the air with a sense of finality, but I saw her brows furrow as her eyes continued to gauge my reaction, almost asking me to challenge it for her own sake. The words hang in the air, clouding the room with doubt and uncertainty.

I was leading a Kaur identity discussion at a Sikh youth camp last year when I heard the above sentiment. I had participated in the same discussion as a camper many years before, and, now, I was returning as a guest, hoping to guide the young Kaurs through some of their struggles, which I remembered all too well. But I was unsure of how to respond to the idea that our whole conversation could be useless, as this young Kaur shared that the males in her family had always taught her that the only portion of Sikhi she should concern herself with is what others cannot see.

When I started wearing a dastaar, I was shocked that for each person that asked me the significance of it, another asked, “I thought only Sikh men wear a dastaar? I’ve never seen a woman wear it before.” I have often heard the argument that our Rehat Maryada says that the dastaar is only mandatory for men, and this often becomes the reasoning at camps for why only the male campers are required to wear a dastaar. Although this is true, I think the messages of our Guru should take priority.

We, as a panth, need to start questioning which values and traditions are moving us forward and which ones are countering the decades of progress for which Sikhs before us fought and lost their lives and sacrificed. We need to remember our history as a people who fought against societal norms. Even though our Punjab is part of a country that cannot even respect women enough to let them walk safely in its own streets, and even though our immigrant generations are part of a society that tells us that women should be weaker and quieter, we need to teach our girls that this is not their path.

The Sikh way of life has always differed from other religions, in that it emphasizes both an internal and external development of self and community. Although Guru Granth Sahib focuses primarily on the developing consciousness of an individual and recognizing our internal divinity, there are also lines of Gurbani that discuss the significance of the physical identity, too.

ਕਾਇਆ ਕਿਰਦਾਰ ਅਉਰਤ ਯਕੀਨਾ ॥

kaaeiaa kirdhaar aourath yakeenaa

Let good deeds be your body, and faith your bride.

ਰੰਗ ਤਮਾਸੇ ਮਾਣਿ ਹਕੀਨਾ ॥

rang thamaasae maan hakeenaa

Play and enjoy the Lord’s love and delight.

ਨਾਪਾਕ ਪਾਕੁ ਕਰਿ ਹਦੂਰਿ ਹਦੀਸਾ ਸਾਬਤ ਸੂਰਤਿ ਦਸਤਾਰ ਸਿਰਾ ॥੧੨॥

naapaak paak kar hadhoor hadheesaa saabath soorath dhasthaar siraa

Purify what is impure, and let the Lord’s Presence be your religious tradition. Let your total awareness be the turban on your head. ॥12॥

— Guru Arjan Dev Ji, Raag Maaroo, Ang 1084

Through our physical identity, we can remind ourselves of the values of Gurbani that we want to instill in our daily lives, but also of the sacrifices and progress made throughout our history. Many Sikhs say that the time they have to tie their dastaar each morning becomes a time of self-reflection to remember the shaheeds that sacrificed their own lives to allow us to live ours with freedom. Each time a person asks me about my dastaar, it gives me the opportunity to reflect upon and share the messages of equality and justice that have been repeated throughout our history. Looking in the mirror, I am reminded that I do not just represent myself on a daily basis, but my entire community and it is my responsibility to reflect internally, as well, to ensure that I am constantly developing and bettering myself as a person and a Sikh.

Source: http://www.sikhnet.com/news/young-sikhs-keep-faith

At another Sikh youth camp this summer, I was asked to be one of the judges for their annual dastaar competition. All campers are encouraged to wear a dastaar throughout the week, even if they have never tried wearing one before; however, only the boys are required to wear one. I was thrilled as the youngest group started off the competition because every single camper, boys and girls, participated. The second youngest group was the same story. However, by the second oldest group—which were the pre-teen campers—only three females participated. The oldest group only had two female participants out of a group of 40 plus campers. Sadly, only one of these five older girls wore a dastaar, or even kept her kes, outside of camp.

I went to sleep disheartened that night. Growing up, and now, camps have always been the “hub” of Sikhi for me. It’s where our most exciting conversations are happening and it is the easiest place to take a peek at the next generation of Sikhs. Although I was excited for the few girls who were trying a dastaar for the first time, I was disappointed that there was not a larger push towards encouraging more girls to do so. I saw the confidence in the younger girls as they strutted down the “runway” we had created for them to show off their crowns, but I saw that same confidence disappear in the older girls as they hid behind their Sikh brothers. Even here, I was seeing the disappearance of the Kaur identity.

Although each person has their own path as a Sikh, we should at least encourage all individuals equally to wear a dastaar, take amrit, and live the Gursikh path. We should encourage aunties to take on leadership positions in gurdwara, not just teach in the Punjabi or Khalsa schools. We should have more women do visible seva roles, like chaur seva, keertan seva, and parshaad seva. Similarly, it should not be uncommon to see men in the less visible roles, like doing seva for langar. We should recognize that the roles in our community are not meant for one gender over any other, and that each individual—regardless of age, gender, sexual orientation, social class, race, education level, or any other distinction—has the right to be a Sikh and be a part of our community. This idea of unyielding love is what our Gurus practiced, and in trying to develop this in our relationship with Waheguru, we must also develop it with each other.

The role of a Sikh has never been to fit into what is popular, but to counter that and move society towards a more equitable place for all. In leaving our Sikh women—or anyone who does not fit into societal standards of normal—behind, we are decreasing the strength of our own community and limiting our own ability to make change. Sikhi has always been a lifestyle of revolution in my eyes. Our Gurus asked us to constantly evaluate how we are living our daily lives, and when something no longer makes sense, it is time for a change. I think in limiting our Kaurs, we are failing to live this revolution.

In trying to reconcile the dichotomy between how our panth currently views the Sikh female identity and what I have understood of our Guru’s message, I found that I cannot and do not believe that our Gurus would have agreed with the sentiment that only men should carry the Sikh identity. Instead, we should support our Sikh youth equally, teaching them to support each other, rather than fighting over whose struggle is greater. In our aspiration to be different and challenge the societal norms around us through the Gursikh path, we all face different struggles, none greater than the other. And if we focus on supporting one another, we can grow as a community, and face these challenges together.

Main Photo Source: BOSS Sikh Camp 2014