In this article, Amrita Kauldher explores historical narratives to understand how South Asian women influenced Canadian culture. She tries to, “present are the faces and bodies of pioneers that slip through the historical record.” She urges readers, “…to look beyond a one-sided gendered story of “turbans” and “beards” for the socio-historical record?”

Points of Entry: Historicizing South Asian Women as Pioneers and Descendants

by Amrita Kauldher

I had never heard the term “Ghadri” until quite recently, actually it was little over a year ago, after attending a conference on the relevance of Ghadri Movements and politics of decolonization. What did I learn? The fight against British imperialism is still heavy on the hearts and minds of immigrants and first/second generation South Asians in North America. The ghosts of imperialism and colonialism continue to knock and are still lingering. They linger in our museums, textbooks, politics, and in the very stories that others tell us about ourselves.

As one of the speakers at this event reflected on her experiences on encountering the Ghadar movement and activism as “stumblings”, “incidental” and “accidental”. Her experiences growing up were very much about assimilating into the American fabric, and de-politicizing herself to become like the “rest”. Because wearing brown skin is hard as it is. I could relate. I can relate to being a “circumstantial activist”. Born and raised in a small town in northern British Columbia, the Punjabi Sikh population was key and influential to the forestry industry. However, I often find myself reflecting on what the community culturally contributed. What was accepted as our ethno-social contribution to the region? Does this community get remembered for the samosas brought to the bake sales? Is it the invitation to the gurdwara during Guru’s birthdays and Vaisakhi?

As a social anthropologist today, and having worked on a social archive of sorts with the local museum through oral-history initiatives, every now and then my thoughts are consumed with what becomes the re-presentation of this once booming community that has almost completed its mass exodus to the west coast of BC. However, what I find more dangerous is an uncompleted oral history project, which will most likely be completed without critical community engagement. It is the danger of misrepresentation, and letting others tell our stories that I fear.

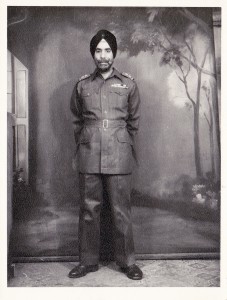

I would like readers to think about the notion of “points of entry” in the grand narratives of what it means to be a South Asian, a Punjabi, of Sikhi heritage and a descendent of the many interpretations of Ghadri in North American. I can’t deny my grandfather’s legacy as the first turbaned Sikh in that town. However, it seems my historicization revolves around his image. Every year Remembrance Day came around he proudly marched in the parade and the local paper did an article on his contribution to the Indian army. He becomes an archival snippet of empire. His humanizing elements of identity channeled through emotion, discomfort, and vulnerability felt through the immigration process are null and void. Having been turned down from numerous jobs in the lumber mills because he wore a turban never accompany the image of him as an Indian subject fighting for the efforts of European allies.

Recently, with the 100th year anniversary of the Komagata Maru “incident” becoming a junction of rallying and remembrance for South Asian communities across Canada, I challenge people to rethink and re-conceptualize that denial of entry. I know for a fact that it is not my point of entry. The focus here is to intersect grand narratives that homogenize ethnic groups, and over-look South Asian women as agents and pioneers.

Policies put in place by the Canadian government literally put a halt to the imaginings of South Asian women as “free agents”. On the 28th of February 1912 the Minister of the Interior of BC, Robert Rogers disapproved lifting any restrictions against “Hindu” women entering Canada. This was two years before the Komagata Maru “incident” took place. From this point onwards not only do South Asian women go missing from the historical narrative, but they become de-politicized. Or so we are made to believe.

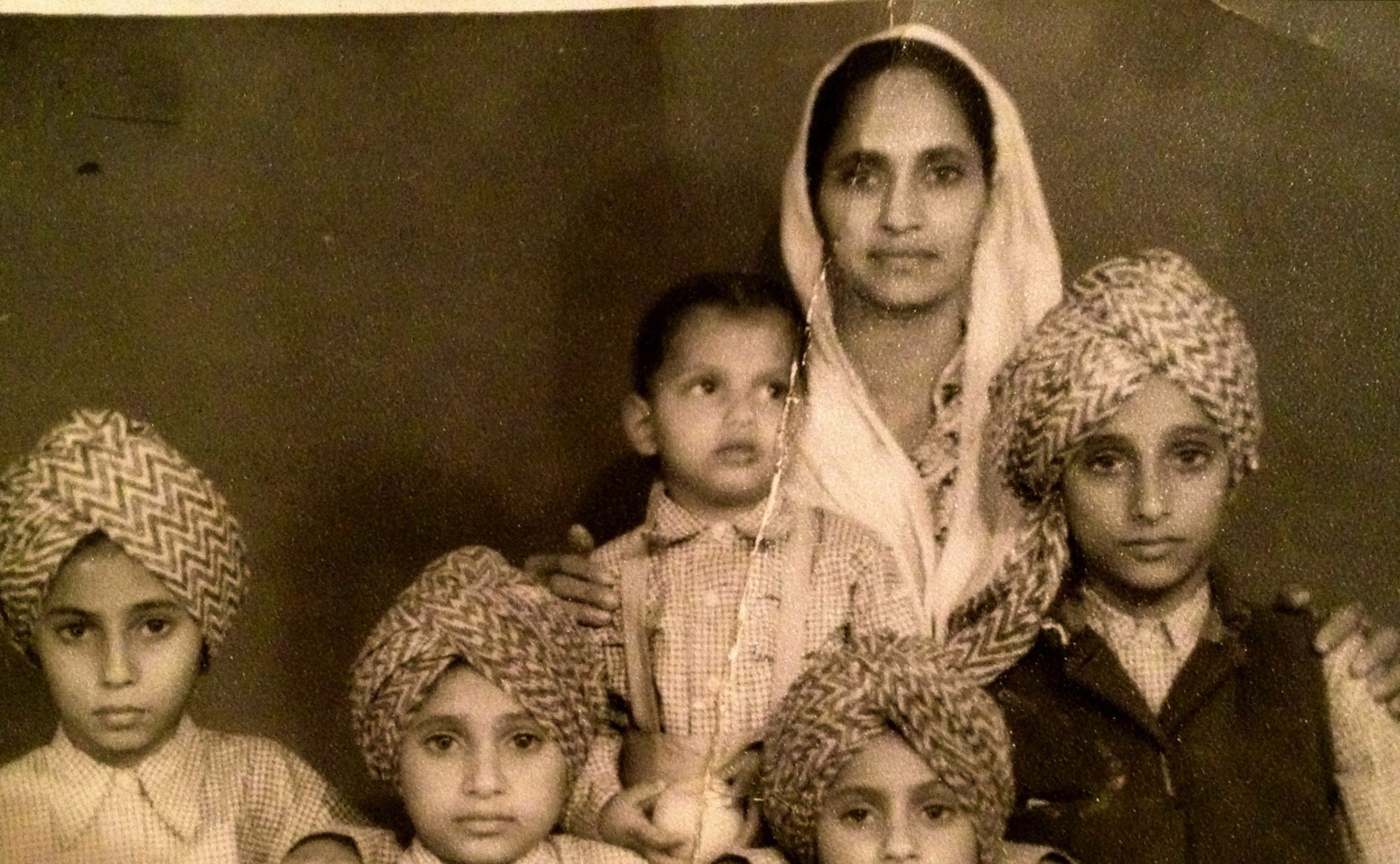

When we think of pioneers and frontiers certain images populate our mind. In attempts to undo dominant images of the Euro-American male, we adopt strategies of producing counter-knowledge. In re-gendering the “frontier” I do not only suggest countering the Euro-American male, but also the image of turbans and beards from small towns in northern British Columbia that were found in lumber mills, farms and railway yards. However, I am not substituting it was sarees, bindis, and dupattas. Instead what I aim to present are the faces and bodies of pioneers that slip through the historical record.

These are the same women, who very much like other women across BC turned on their televisions at 3 in the afternoon, and sat down to watch American soap operas with a cup of tea. The only difference is their tea had the aroma of cardamom. Soon after their soap operas were done, they prepared dinner, tended to children, and also sat down at dinner tables and discussed their daily events. They were not just South Asian, or Punjabi immigrants. They were unwaged labour, and the reproductive force. They were negotiators of culture that influenced their children. Most importantly, it is because they are women, and secondarily immigrant women that they are political. Their abilities to reinvent themselves, hold on to certain traditions, refashion clothing trends to fit their life style, speak their own versions of English made them transnational. I cannot speak for all women, but my grandmother, aunt and mother embodied, and participated in what it means to be a transnational citizen. They were and continue to be political.

To be political doesn’t require one to be the overt “academic” or “leftist”. In this case politics was written all over their bodies. From their skin, hair, clothes, accents and their very presence. To some extent these women were matriarchs. They were looked up to, and most sought their advice. Their politics was both private and public.

So, if the larger significance of Ghadar politics and Ghadris today is solidarity among the marginalized, re-claiming the historical record, and politicizing the representational violence done unto black and brown bodies. I say yes to this movement. However, I would like to remind those willing to listen, that it might be time to re-gender politics of reform. We have largely underestimated the social and cultural reformations South Asian women have embodied, practiced and produced as pioneers. Can we continue to look beyond a one-sided gendered story of “turbans” and “beards” for the socio-historical record?