by prabhdeep singh kehal

I began writing to discuss one topic: how Sikhi guides Sikhs on valuing the body and mind and how Sikhi guides transgender and queer Sikhs to understand the meaning and purpose of the body and mind. I wanted this conversation to happen based on how transgender, queer, and femme 1 Sikhs confront the world, or what is also called learning from “transgender embodiment.”

Instead, in Sikhs’ understandings of the body, I constantly kept coming up against a strictly material obsession with the body. This material obsession meant that conversations started and ended with how to manage the body’s outward appearance. Because the conversations began there, they rarely reached moments where we could ask what the body’s full role was in our journey towards the Guru.

I realized our current approaches to Sikhi prevented us from understanding how Sikhi guides us towards spiritual liberation more fully, let alone understanding what this could look like when informed by how transgender and queer Sikhs confront the world. But what do I mean when I say “how transgender and queer Sikhs confront the world?”

Reconsidering a Duality of “what we do with our bodies” and “what we do to our bodies”

Satinderpal Kaur put it eloquently during a conversation when we were discussing the purpose of this human life/body: “What we do with our bodies matters, but the world is out here judging what we do to our bodies instead. And Guru Ji reminds us, it is what we do with our bodies that matters.” Importantly, we discussed how there is no actual duality between these orientations when it comes to our lives; this is what Sikhi teaches us. What we do with our bodies is informed by how we understand the world and its history; these understandings are then translated into the value systems we use to determine what to do to our bodies. Similarly, what we do to our bodies is informed by the materials and knowledge available to us. From what is readily before us, we can choose what to do with our bodies in service of liberation. In rejecting the duality between these orientations, Kaur’s statement focuses us on how we embody our existence in this life.

When people focus on what to do to our bodies as the sole basis for understanding their body, rarely is there a lesson to learn from what is materially right in front of us For example, a common experience among children – regardless of gender identity – is gender play, or being able to explore what we, as older people, call gender roles. To children, they are simply making choices on how to manifest an inner desire and they are using what is available to them to do so; this can continue beyond earlier childhood, as well, as children keep learning. Like us older people, they too are still learning how people who look and act like them are treated based on our actions.

But in their youth, a transgender Sikh child is learning for the first time whether or not they would be supported or loved if they disclosed some inner yearning. In our Sikh communities, we often discuss how to transcend our material obsessions of this world. For some, this leads to a complete rejection of discussions of materiality, even though materiality influences our understanding of what “transcending materiality” means. The Sikh child who engages in a type of gender play is now labeled as engaging in manmat because parents may only notice gender play when their child’s behavior deviates from what they think is appropriate for their child’s presumed gender. Or, parents may even think letting their children explore is the same as leading their child and family away from the Guru and Sikhi. How do we begin to explain to parents that transgender kids often have a sense of their developing gender identity before they socially transition in some way (e.g., telling others about a change in their pronouns or changing their external presentation).

In contrast, when people begin at a different starting point, such as focusing on what to do with our bodies, this complexity – life – is transcended by acknowledging and working with it. For example, what if we thought about what a condemnation would do to our families when we condemn or punish a Sikh as defying the Guru because they are engaged in gender play? Not knowing how to properly respond cannot be a reason to rely on gender disciplining. Would this condemning and policing bring our child – and you – closer to the Guru? Based on what reasoning? In my experiences, Sikhs will allege that “transgender issues” are issues for white, Western, or wealthy communities in the United States as a way to delegitimize these topics within our diasporic communities. Yet, our children go through similar processes. It may simply be a lehenga, salwar kameez, or kurta instead of a skirt or dress shirt.2

Though both approaches (do to and do with) recognize that the body plays a role in building a Sikhi-centered life, they frame the question of right and wrong in fundamentally different ways. While the former approach focuses on naming and managing a duality of right and wrong bodily management with “right” and “wrong” being static categories for eternity, the latter approach focuses on existence’s complexity and considers it an invitation to learn what could be “right” and “wrong.” We have to make choices as Sikhs regarding how we want to live in this world, but which choices do we condemn from the outset because knowledge makes us uncomfortable or shameful?

Guru Ji regularly referred to the material world as an illusion because They told us of the anand that awaits; They also told us we had to live in and understand this material world. Though some of us may argue that this means every conversation should begin with determining what is a right and wrong action to do to our bodies as Sikhs, it is not a separate question from what a right or wrong action is to do with our bodies as Sikhs. If you believe gender play or homosexuality is wrong, does that belief justify all your attempts to condemn transgender and queer experiences – from our experiences with intra-community sexual violence, the threat of homelessness, the lack of healthcare, and forced marriages?

Regulating the Bodies of Transgender and Queer Sikhs

These prior discussions are, of course, simplifications. As Sikhs justify or rationalize their daily choices as “in line with Sikhi,” they teeter between these approaches when they confront different life circumstances. But one of the few times that the Sikh communities seem to come together – across caste, geography, gender, faith practice, and class – is to focus exclusively on what to do to our bodies.

The topic of bodily regulation is not a new conversation, though its connections to transgender and queer experiences has often been less discussed. Throughout our known and unknown histories, many Kaurs have written, fought, struggled, and died discussing these topics of body regulation as it has related to Kaurs. By current definitions, many Kaurs within our own family histories and communities could be considered queer or transgender themselves today – did we ever consider that when we collectively remember our ancestors? If we value transgender and queer experiences, we must understand that part of queer and transgender Sikh experiences in confronting this world is knowing our transgender and queer ancestors must have married into opposite-sex marriages – whether consensually or for survival. We understand that we may not know everything about queer and transgender Kaurs because we have had to hide how we understand ourselves – using whatever was available to us, including marriage. As we all consider how this changes our understanding of Sikh history, Sikhi, and our family histories, I turn to one shabad to guide us.

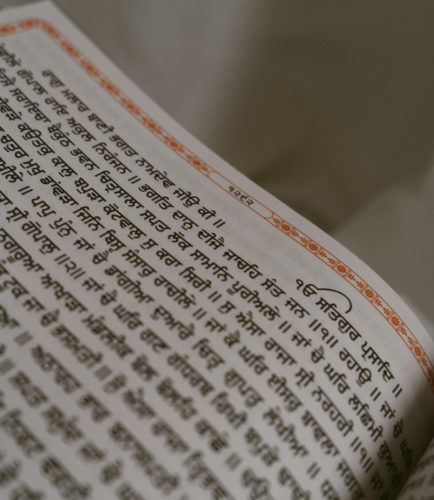

In raag ਮਲਾਰ (Malar), Bhagat Namdev Ji is in conversation with Guru Ji3 , Aang 1292:

ਆਲਾਵੰਤੀ ਇਹੁ ਭ੍ਰਮੁ ਜੋਹੈ ਮੁਝ ਊਪਰਿ ਸਭ ਕੋਪਿਲਾ ॥ ਸੂਦੁ ਸੂਦੁ ਕਰਿ ਮਾਰਿ ਉਠਾਇਓ ਕਹਾ ਕਰਉ ਬਾਪ ਬੀਠੁਲਾ ॥੧॥

ਮੂਏ ਹੂਏ ਜਉ ਮੁਕਤਿ ਦੇਹੁਗੇ ਮੁਕਤਿ ਨ ਜਾਨੈ ਕੋਇਲਾ ॥ ਏ ਪੰਡੀਆ ਮੋਕਉ ਢੇਢ ਕਹਤ ਤੇਰੀ ਪੈਜ ਪਿਛੰਉਡੀ ਹੋਇਲਾ ॥੨॥

the temples’ inmates under the illusion of my low caste were offended with me ॥ calling me sudra they pushed me off Father Vithal (name of Vishu) what shall i do ॥1॥

should You grant me liberation after death none of them shall know ॥ this manikin of a brahmin calls me untouchable thereby does Your glory recede ॥2॥

In this lesson, Bhagat Namdev Ji calls to the Guru. The caste of Brahmins4 – a self-constructed dominating class of religious leaders who determine the right and wrong way to be a devotee for spiritual liberation – evicted Bhagat Ji from their Guru’s home/temple. As they evicted Bhagat Ji, these Brahmins invoked caste apartheid law. Brahmins used the status of caste, which they themselves made, to exploit another group of communities: these Brahmin mannequins prevent those who they deem as wrong from achieving spiritual liberation. Guru Ji tells us that our acceptance of caste – and any other label of existential inferiority – leads Their devotees to lose the Guru’s glory, just as these Brahmins did.

Importantly, caste apartheid was and is a matter of what people did with what they had available. Brahmins claimed exclusive access to liberation, and they distributed these benefits according to caste; caste-base discrimination became apartheid when it became a synonym for law and order in society. We can now ask, what is the difference in practice between these Brahmins and those Sikhs who also ignore the complexity of life? The Brahmins ignore the world’s complexity in order to enforce their duality of right and wrong, and those Sikhs also ignore the complexity of life to focus exclusively on what to do to our bodies, especially for regulating femininity, queerness, and transgender Sikhs. And, for those who must navigate the pervasiveness of caste-oppression in our Sikh communities, the condemnation of femme, queer, and transgender Sikhs multiplies our investment in caste because it continues stitching together oppression based on gender, color, labor, and existential liberation. Do these Sikhs not claim control over spiritual liberation and then use the material and knowledge available to them to name an inferior Other?

At this point, most will start pushing back against me when I say that the present-day regulation of gender among Sikhs is akin to Sikhs’ management of who can be liberated through Sikhi. Some will cite images of “fixed” gender identity from Sikh history as counter evidence. Rarely, though, do they acknowledge that these pictures are the ones that have survived. How do we know what we have lost if we cannot know that something is lost, let alone if something was strategically not created or destroyed to maintain the existing system? Others will invoke shabads or one of the many versions and interpretations of rehat to suggest that we have been told how to act and deviance from that is manmat. Personally, the second defense is my favorite because Guru Ji already told us what to do when we confront things that appear to us as contradictions. Rather than condemnation, we do not ignore what is right in front of us and not try to understand new information, as if we are controlled by some idols. In the same shabad, Bhagat Ji continues their conversation with Guru Ji:

ਤੂ ਜੁ ਦਇਆਲੁ ਕ੍ਰਿਪਾਲੁ ਕਹੀਅਤੁ ਹੈਂ ਅਤਿਭੁਜ ਭਇਓ ਅਪਾਰਲਾ ॥ਫੇਰਿ ਦੀਆ ਦੇਹੁਰਾ ਨਾਮੇ ਕਉ ਪੰਡੀਅਨ ਕਉ ਪਿਛਵਾਰਲਾ ॥੩॥੨॥

You are known as compassionate and gracious and long are Your arms ॥ The Divine turned the temple-door towards Nama (Namdev) and the petty brahmin stood repudiated ॥3॥॥2॥

Guru Ji reveals to us that our liberations should not come at the vilification or condemnation of another, especially when based on historic condemnation through caste logics. But in addition to this, Guru Ji intervened and turned the institution devoted to Them around in order to serve those who the Guru’s devotees had deemed as unworthy. The Guru took what Their devotees valued and put it in service of the liberation of the excluded. Those who were marked inferior were not only linked to Sikh collective liberation, but their liberation was made necessary for our own.

From Duality to Imagining New Unities

In conversations on bodily importance for Sikhi, Sikhs against acknowledging transgender and queer Sikhs transform our desires for affirmation into sacrilege. To these folks, our bodies are separate from ourselves, as things to be managed; our desire to have our bodies resonant with our spirits is seen as an impure management decision on our way to the Guru, rather than a spiritual desire manifesting through the body. This is in spite of the fact that this manifestation of the spiritual through the body is exactly what the traditional Sikh baana, such as the dastaar and the practice of maintaining kesh, is. Yet, any acknowledgment that gender affirmation surgery for transgender Sikhs could be a form of coming into our fuller selves worries some Sikhs5 . To them, considering these topics together demeans the Sikh purpose of the body because the body is meant to be regulated and discussing the topics together moves the focus towards deregulating the body. But, what we experience from these debates is primarily cisgender and heterosexual (and occasionally homosexual) Sikhs telling us our body and mind are separate and must be made one in the form they deem right per their selective reading of history and Gurbani. Meanwhile, we tell these same individuals that we are making our body/mind into one form to no real acknowledgement or willingness to understand. Like other Sikhs, we are on a journey to continue bringing that union into full view, and this does not take one shape or form.

Our Path in this World

Much like Bhagat Namdev Ji, we have been in consultation with our spirits. In conversations with the Guru, Guru Ji provided a path for Bhagat Ji; we are telling you Guru Ji has offered us a path too. No one is compelled to take it for themselves, but it exists. If Guru ji Themselves intervened to reorient the institution made for Them on this earth in order to include and understand those that Their devotees made inferior, how can Sikhs today claim that transgender and queer Sikhs are pursuing manmat when they pursue gender affirmation? Not all transgender or queer Sikhs have the same needs and “affirmation” may mean different things to people; this is the beauty of the Guru’s complexity. Yet, those that do seek these services, or any support, are sent away from Sikhi just as the Brahmins sent away Bhagat Ji. Why do cisgender and/or heterosexual Sikhs not question why they are linking their liberation to our inferiority, then, rather than asking transgender and queer Sikhs to prove their worth or legitimacy to cisgender and heterosexual Sikhs?

This is how we have had to confront the world. We decided on our path in this world: using the material and knowledge available to us to find the Guru already within us. We knew it would be a hard path in this world, but we knew the Guru was with us. Because who else has been there from the start, guiding us as we worked toward spiritual liberation? Cisgender and/or heterosexual Sikhs may not be ready to share in the Guru’s gift through our lives, but that is their choice to make. And it shouldn’t end in violence towards us. For us, our caravan is ready, and we are okay proceeding alone if we must6 . We know Guru Ji turns Their institutions towards those whom Their devotees condemn.

Call To Action

Naturally, after reading that what we do with our body needs greater focus in our Sikhi-based conversations, what do we do with our bodies to support transgender, queer, and femme Sikhs? For instance, in a recent presentation to Sikhs, Black transgender and queer activists and scholars shared how to be more involved in this moment of social justice. Though there is not a singular answer on what to do (yes, that can be frustrating), it begins at home and in your local sangats. Consider the following situations.

If someone disclosed their gender or sexual identity to you today, do you know the local centers you could go with them to for support, resources, or services? What types of affirmations do you give children or adolescents? Do you link goodness with particular types of gender roles? Do you tell them that they should not act like particular types of girls or boys, or call them “gay” or “hairy” as a joke? Did you do nothing when your sibling, parent, or friend made jokes or statements like this to someone else? Are Kaurs “goods girls” and Singhs “good boys” but “bad” the moment they deviate from your expectations?

Or within our sangats, have we begun conversations about ongoing sexual assault or predators who target youth of all identities, and how to build support and safety systems for them? These issues affect transgender and queer Sikhs, as do conversations about anand karajs. Are our Gurdwaras safe enough as centers of our communities to offer housing support, especially if transgender and queer Sikhs get unhoused by their birth families? Or at work, if you have access to salaried jobs with benefits, are the benefits inclusive of trans-affirming care? These are the types of activism that transgender and queer Sikhs are doing outside and within Sikh communities, as we’ve had to organize ourselves in face of our communities’ Othering.

To begin thinking about your role in supporting transgender, queer, and femme Sikhs, consider what is available to you and what is within your abilities to do (resources for education inclued in the caption of this video). Community organizer and scholar Harleen Kaur created a guide to help people think about their role in the fights for liberation through Gurmat principles. Whether that means youth taking a greater role in Gurdwara governance or using the Gurdwara and community resources to build services for social change locally with other communities, the work you do with us matters. This may mean that you commit to regularly having new conversations with someone at your Gurdwara or homes to fight taboo and stigma, both of which make staying hidden a main source of safety. It may mean that you shift how you distribute your volunteer time between Gurdwaras and local organizations, to which you could donate financially or with labor. There are already organizations supporting transgender and queer people in major cities and towns where Sikhs reside across the nation and Sikhs could partner with them (38 states have Gurdwarey, in particular states with large sangats: California, Texas, New Jersey, New York, Washington, Virginia, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania). Working together, we could address problems of humans being unhoused, a lack of job security, and lack of access to health insurance. Depending on what your communities have and need, your role will be different.

Finally, as we continue our respective journeys towards reunion with Guru Ji, all of this raises questions of how to determine “right” or “wrong” action in our present days. If we link our struggles with feminist struggle for equality, it should include questioning our own commitments to racism through our daily actions. And if we consider history and Sikhi, then caste remains a persistent issue for Sikhs to challenge in our lives. Though I discuss how stigmatizing queer, transgender, and femme Sikhs intersects with how our communities have been socialized within centuries of caste apartheid logics, I am not making a statement of equivalence. Rather it is a statement of relation. For instance, thinking relationally, we can ask why anand karajs take up so much debate time among dominant caste Sikhs when we rarely discuss the meaning, history, and purpose of anand karajs as part of creating a Sikhi-centered life. As a result, the anand karaj has been molded to fit into a western, Christian nation-state model across the western diaspora. If we think of it in relation to how our communities have treated issues of caste and marriage, perhaps the focus is connected with how marriage serves as caste closure for dominant caste families to maintain their control of material resources. Or, perhaps caste logics inform our understanding of why gender variance and homosexuality are considered “inappropriate” for some communities because it is a mark of deviance. If the defense of marriages and anand karajs is based on resource hoarding or caste-based ideas of gender normativity, then Sikhs must reconcile how this obsession with materiality is consistent with their Sikhi.

As transgender and queer Sikhs fight for their legal rights to exist as part of contemporary societies across the globe, one means to do that is challenge colonial state structures that criminalize sexual difference, as has been done by activists in India with the repeal of Section 377. Yet, even then, the remaining structures still transfer property via patriarchal bloodlines and marriage laws; this was a reason why transgender and queer revolutionary activists from the 1960s and 1970s in the United States resisted making marriage the priority and instead focused on ensuring that livelihood needs were met instead. Hence, inclusion and incorporation on their own are limited in guiding us towards mukti. Everyday, each of us have decisions to make about how to follow our paths. One of those decisions is how we make our path towards the Guru dependent on subjugating those who we may not want to or struggle to understand.

Photos are by Tajinder Kaur . © 2020 All rights reserved.

I thank Satinderpal Kaur and Lakhpreet Kaur for their comments on earlier drafts of this piece.

Footnotes

1 – Queer is used here in the political sense as defined by Cathy Cohen in her 1997 article “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics”, which centers the uplift of the marginalized in society. Trans or transgender is often used as an umbrella term for folks whose gender identity does not conform to definitions within the Western, biologically-essentialist notions of gender (e.g., genitalia = gender identity). To learn more about how nation-states historically have used biologically essential definitions of gender to oppress anyone not considered a man, consider Lugones’ “The Coloniality of Gender” and Oyewùmí’s “The Invention of Women.” Because colonial patriarchy is still a material reality for girls, women, and femmes globally, patriarchal violence is a reality with which we must all contend (i.e., violence done to maintain power for those empowered as men), especially when agents of violence use biology to enact violence (i.e., femicide and sexual violence that occurs across genders). For that reason, I have included femmes in my list as a way to honor how femininity is used to enact violence across genders. Furthermore, this opens the space to discuss how “Kaur” itself may be the Sikh, non-colonial, non-essentialist concept of “womanhood” that a new generation of Kaurs are fighting to make today.

2 – Though I do not fully explore gender fluidity and gender binarism in this piece, I provide some context into my thinking in a prior interview, group podcast, and individual podcast. It is also helpful to keep in mind how gender has been fluid over the course of world histories.

3 – Core translations are humbly done by Bhai Gurbachan Singh Tlaib, who focuses on interpreting Gurbani within the philosophical context the Guru’s spoke, not in western and colonial Christian frameworks. I provided moderate, stylistic changes for comprehension.

4 – It is worth recognizing for Sikhs that even as our Guru’s rejected caste apartheid from Sikhi, Sikhs have accepted caste apartheid as a way to navigate the world. Though some Sikh cultural practices may not engage with the Hindu-based varna system, different Sikh diasporas hold onto biologically-based heritages. These heritage-based communities may refashion caste apartheid logics as cultural preferences within communities, without ever questioning if caste apartheid logics are separating these communities. For more on caste apartheid, consider Ambedkar’s “Annihilation of Caste” as an introduction.

5 – Though the entire piece is meant to help frame conversations on bodily surgery and hukam, I recommend this interview with Laverne Cox and Katie Couric on understanding how even that question begins with what to do to our bodies, which I argue limits our understanding of liberation (begins at 3:50). For more context, Couric apologized for this line of questioning and re-did the interview appropriately.

6 – This is in reference to shabad: ਗਉੜੀ ਬੈਰਾਗਣਿ ਰਵਿਦਾਸ ਜੀਉ, Ang 346.

About prabdeep

prabhdeep is a writer, community scholar, and educator. As a sociologist and doctoral candidate at Brown University, prabhdeep researches how people and communities make knowledge about race and racism, and how they use this knowledge in their lives. prabhdeep’s community work focuses on identifying and fighting how ideologies of white supremacy, anti-queerness, and gender conformity emerge in our lives, both within and outside the Sikh and Sikh-American diaspora. They dream of futures filled with community libraries.

About Tajinder

Tajinder Kaur is a photographer based in Montreal. You can find her work on her Instagram.

1 Comment

Jaspreet

11/13/2023 at 5:12 pmThank you for this wonderful resource. I have often thought through some of these topics and the way gender felt so very fluid to me growing up and listening to gurbani. Your words put together a concept that I have been trying to materialize for the last 5 years. Thank you again for sharing your thoughts 💕